by John F. Mramor, MA, LMT, CLT, NCTMB, CR, RM

This is the first part of an article about Ascites and its manual treatment, submitted to JMS by John F. Mramor, LMT. At the beginning I would like to mention the quality of the article, the author’s expertise, his ability to analyze theoretical aspects and clinical observations and his dedication to the profession. We at JMS understand that the topic of Ascites and its treatment isn’t first priority information for many readers. However, we encourage them to read the article for several reasons.

1. If readers practice or are interested in the clinical aspects of Medical Massage articles like this one, it contributes to their overall professional expertise by extending horizons and pointing to new directions.

2. The article greatly illustrates what an incredible tool Medical Massage is and what it can do for patients.

3. Readers may encounter patients, family members or friends who may need this kind of help right now or in the future. This article provides clinical guidelines for just such an event.

4. If your practice is connected with Hospice or any palliative care facility, this is simply a must-read article for you.

I hope you will learn a lot from the article and from the author’s personal experience and expertise, just as I have.

Dr. Ross Turchaninov, Editor in Chief

Medical Advisors of the Article:

Michael Harrington, MD Director of Palliative Care Consult Service,MetroHealth Medical Center,

Assistant Professor, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

Walter George, MD

Medical Director, Crossroads Hospice,

Cleveland, Ohio

ASCITES. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Ascites is an accumulation of fluid in the abdomen or to be medically correct, “in the peritoneal cavity.” Generally speaking, ascites is a form of lymphedema (13). By using the principles incorporated in lymphedema management, as the author proposes, ascites can be mobilized manually.

Ascites has three main causes:

1. Liver cirrhosis

2. Cancer (ovarian, breast, colon, stomach, pancreatic, liver, uterine, lung, prostate) (28)

3. Intestinal disturbances

In 50% of patients with cancer, ascites develops a secondary to metastatic invasion of the visceral peritoneum (15). Peritoneum is a serous membrane which lines the walls of the abdominal cavity and the surrounding inner organs.

ASCITES DUE TO LIVER CIRRHOSIS

Ascites is a major complication of liver cirrhosis, occurring in 50% of all patients. Its appearance signals a significant negative development in the course of cirrhosis since it foreshadows a 50% mortality rate (9).

Cirrhosis is the clinical outcome of various pathological conditions: viral infection, excessive alcohol consumption, blockage of bile drainage, congestive heart failure, drug related damage, etc.

The main feature of cirrhosis is chronic inflammation of liver tissue called parenchyma. Cirrhosis damages liver cells called hepatocytes and causes scarification of parenchyma with following irreversible loss of its function. Damage of hepatocytes and a decrease in their normal mass causes a variety of complications, including ascites.

Portal vein drains venous blood from the entire gastrointestinal system as it enters the liver which cleans blood from toxins before returning it back into circulation.

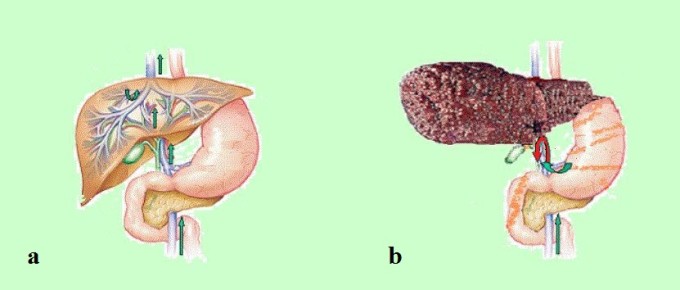

If due to hepatocytes’ death and parenchyma’s scarification the liver is unable to drain and clean all blood from the portal vein, it causes a condition called portal hypertension or an increase of hydrostatic pressure inside of the portal vein and retrograde flow of venous blood. Fig. 1 shows drainage through a healthy liver (a) and a liver affected by cirrhosis (b) with portal hypertension indicated by the down pointed arrow.

Fig. 1. Portal drainage through a healthy and a cirrhotic liver

a – healthy liver

b – liver cirrhosis

red arrow in part ‘a’ – retrograde flow

The formation of cirrhotic ascites is a consequence of a drainage failing via portal circulatory system that results in an accumulation of fluid managed by an otherwise healthy lymphatic system that becomes slowly overburdened (11).

In healthy patients who are not fluid compromised, the thoracic duct (major lymph draining route) is capable of routing up to one liter of lymph per day. However, in cases of cirrhotic ascites, 8 to 10 liters per day are commonly routed and it has been discovered that the flow can approach 20 liters in a 24-hour period (13). This is a compensatory mechanism which the body uses as a detour lymph to unload a damaged liver.

Eventually, as the system of lymphatic drainage works at its utmost capacity from one day to the next, it slowly becomes dilated and varicose. It is only when the increased production of lymph exceeds the ability of a compromised and exhausted system to drain it that ascites becomes observable.

At this point, fluid begins to escape through the dilated walls of portal vein, hepatic capsule and it seeps into the abdominal (peritoneal) cavity which has a volume of approximately 20 liters.

Accumulation of the fluid in the peritoneal cavity increases pressure there and it compresses vena cava, triggering formation of peripheral edema especially in the lower extremities (3).

CHYLOUS ASCITES

For the Manual Drainage Therapy (MLD) of ascites another topic is very relevant – Chylous Ascites. The reason it is labeled chylous is due to the addition of chyle in the ascitic fluid located in the abdominal cavity.

Chyle is a milky substance comprised primarily of long-chain fatty acids (triglycerides). Under normal conditions, chyle is carried by the lymphatic vessels of the small intestine to the cisterna chyli where it is then transferred through the thoracic duct to the circulatory system at the left subclavian vein.

Most often, chylous ascites is the result of a resistance to the lymph flow somewhere within the abdomen or the thorax when chyle escapes lymph and saturates the fluid which is already in the peritoneal (abdominal) cavity. Chylous ascites can also result from damage to the thoracic duct.

The chylous ascites may resolve completely through specialized diets that eliminate the ingestion of long chain fatty acids and surgery to get rid of obstruction in combination with application of MLD.

ASCITES’ GRADES

There is a grading or staging sequence to assist clinicians in determining the severity of the ascites. Like defining the stages of an edema, a sequence has been developed for describing the intensity of ascites, as follows (17):

1+ detectable, but only after a careful exam of abdomen

2+ a small volume easily detectable through observation of the abdomen

3+ quite obvious, but not tense (tense means that abdomen is firm to the touch)

4+ tense

CLINICAL SYMPTOMS AND COMPLICATIONS OF ASCITES

The great clinical importance of ascites and its early management using all possible tools including Manual Lymph Drainage is illustrated by the following medical statistic. Once ascites becomes refractory to medical treatment, 50% of patients die within 6 months and the remaining 50% usually die in less than a year. At this point various medical interventions (abdominal tap or paracentesis, catheters etc.) do not improve survival rates (9, 4, 15, 17).

In the author’s experience, the longest a patient survived with ascites (cirrhotic) and various interventions to manage it was ~2 years. A three year survival rate is less than 10% (2). Effectively, the diagnosis of ascites is almost a death sentence. This is why its early integrative management is such an important matter.

The main clinical symptom of ascites is accumulation of fluid in the abdominal cavity and distention of the anterior abdominal wall. When the fluid volume equals or exceeds >500 ml, the patient becomes symptomatic (6) and with two liters of fluid in the abdomen ascites is clinically visible with bulging flanks. In ascites refractory to treatment, a much greater amount of fluid may accumulate in the abdominal cavity (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Severe Ascites

Here are other symptoms exhibited by patients with ascites:

1. Shortness of breath and difficulties of breathing due to increased diaphragmatic compression (8, 13, 18, 6)

2. Loss of appetite and/or indigestion, constipation, increasingly poor nutrition and nausea due to gastric and intestinal compression (8, 13, 6)

3. Fatigue and loss of sleep (13, 6)

4. Ascites interferes with balance and movement. There is reduced mobility (19)

5. Psychosocial and emotional distress occurs due to body/self-image issues. This leads to anxiety and depression. With the disease’s progress the fear manifests more and more as ascites becomes a “constant reminder” of the disease and a marker of approaching death (13, 19)

6. Urinary urgency (6)

Ascites causes a huge variety of debilitating secondary symptoms:

1. Slowly spreading subcutaneous edema on the flanks, lower extremities, chest

2. Cardiac abnormalities first due to the heart displacement and later congestive heart failure

3. Bacterial peritonitis

4. Peripheral edemas in lower and in severe cases upper extremities

5. Right side pleural effusion (accumulation of the fluid in the pleural cavity with following lung compression)

6. Abdominal, inguinal, diaphragmatic and scrotal hernias

7. Esophageal varices

SYMPTOMS MANAGEMENT

Ascites is not easy to manage, but there are numerous treatment options for it. To be blunt, the only method to completely eliminate the fluid accumulation is to eliminate the cancer or cirrhosis. But of course, this is not a realistic option at this point.

In reality, given the fact that most patients with ascites are considered terminally ill and categorized as either hospice or palliative care candidates, the use of these procedures should be individualized and minimized due to poor general life expectancy (15).

Treatment efforts should focus on symptom control and supportive measures rather than on definitive therapies (6). The very best treatment should offer few side-effects and aim to reduce morbidity associated with the swelling (13), keeping in mind that the least restrictive experience for the patient during his/her final months of life is the preferred option.

DIURETICS

Ascitic fluid is comprised of lymph which is protein rich. Diuretics only remove water, leaving the proteins in the abdominal cavity. As this continues, the level of proteins there rises dramatically and they are massing together, creating fibrotic material which may cause intestinal blockages.

Another issue is peripheral edema and in the author’s experience it is a very tricky subject. For the palliative care patients in hospice setting the peripheral edema does not always respond to diuretic therapy. The main reason is peripheral edema may not be edema, but lymphedema, and this condition is not responsive to diuretic therapy at all. In fact, diuretics often make it worse. As explained previously, diuretics do not remove the proteins and as they remove water, concentration of proteins rises and according to the laws of osmosis it attracts more water increasing ascites. This is why compression using the elastic stockings must be part of peripheral edema’s management.

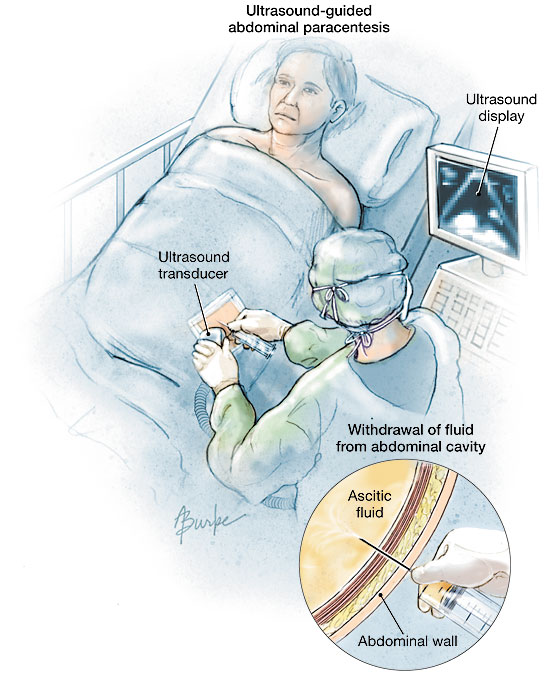

PARACENTESIS

Paracentesis or abdominal tap is the oldest form of therapy for ascites. Typically, taps occur approximately 15 cm lateral to the umbilicus, low enough to avoid the liver or spleen, in what is known as the right/left lower abdominal quadrant (9). Ultrasound guidance is typically utilized in order to determine the best site.

Fig. 3. Paracentesis or abdominal tap

Of course, there are complications and side-effects, but in the author’s experience, paracentesis is a quick, safe and effective treatment to reduce ascites. It is actually more effective than diuretic therapy, less expensive over time and is associated with a lower incidence of side-effects and hepatic problems (4, 5, 14, 17).

For most patients with ascites in hospice and palliative care in North America, paracentesis and diuretic therapy are the most likely to be utilized above all other therapeutic interventions.

The main dilemma with paracentesis is that it is only a temporary solution to an ever present, gradually worsening and incurable problem. The relief is transient and the fluid does re-accumulate. This re-accumulation usually occurs with a vengeance as ascitic fluid tends to fill the peritoneal cavity more rapidly with subsequent punctures (8, 13, 6).

On average a seven liters draw will be repeated every 26 to 28 days given one gram of sodium intake daily; every 13 to 14 days if two grams are consumed (14). However, this fluctuates according to each patient’s disease progression. It is not uncommon to hear of cases that eventually require weekly or twice weekly taps in order to maintain comfort (15).

SHUNTS ANDS CATHETERS

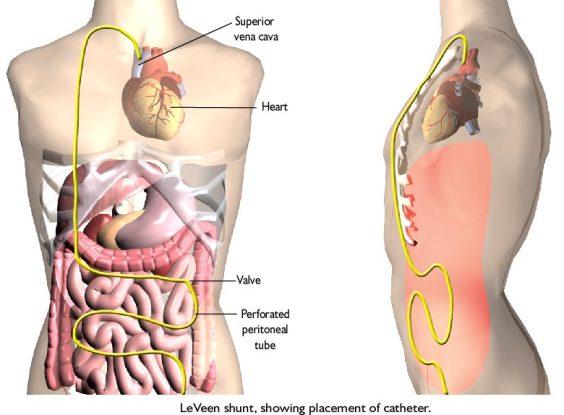

The Peritoneovenous Shunt was originally developed to treat patients with diuretic resistant cirrhotic ascites. Fig. 4 illustrates peritoneovenous shunt.

Fig. 4. Peritoneovenous shunt

It consists of a tube, one end of which is punctuated with numerous openings and connected to a one way valve. This end is implanted into the peritoneal (abdominal) cavity. The tube then traced under the skin up to the neck, inserted there into the internal jugular vein and carefully pushed into the superior vena cava.

The ascites fluid is “pumped” through this tube by the pressure differential between the peritoneal (abdominal) cavity and the right atrium. Thus, it continuously transfers ascitic fluid back into the general circulation.

Despite of its effectiveness, the implementation of this device comes with considerable risk and a staggering number of complications (10, 15). It is rarely utilized with ascites associated with the high protein concentration in the fluid, since clogging of the shunt by accumulated proteins is extremely common and a frustrating problem.

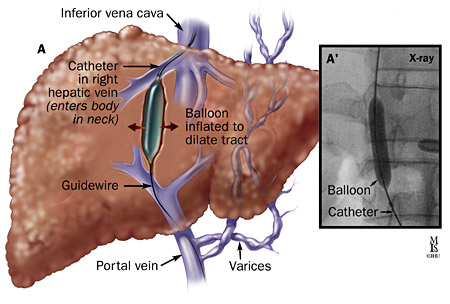

The Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) is a surgical procedure which creates an artificial channel within the liver that allows fluid to flow between the portal vein and the hepatic vein. This flow thus reduces portal hypertension (15). Fig. 5 illustrates the installation of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Fig. 5. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

This procedure is considered superior to that of paracentesis and as becoming the standard of care in controlling refractory ascites (16, 29). TIPS is best utilized as a bridge to liver transplantation or as a second-line therapy (15, 16).

There are numerous other devices that can assist the patient. Ascites drained by implanted catheters may be preferred to repeated paracentesis, although use of a shunt is falling out of favor due to the multiple complications involved. In the author’s experience, paracentesis remains the favored treatment.

CHEMOTHERAPY

Utilized only for malignant ascites, this therapy is not yet a standard treatment option. The procedure involves the introduction of various agents directly into the peritoneal space through a catheter. The purpose is to cause irritation of the exposed peritoneal surfaces in order to produce scarring and fibrosis (6). Most clinicians are finding the success of this procedure dependent upon the sensitivity of the tumor (13). So far, it seems to be eliminating ascites in most of the people treated (8). However, since it remains a newer treatment, further clinical trials are necessary.

COMPRESSION

Nancy Preston, a British nursing researcher, offered the application of the abdominal binder as a method to delay the re-accumulation of malignant ascites. The basic premise is to intermittently raise the intraperitoneal (intro-abdominal) pressure through the use of deep breathing exercises while an abdominal binder applies external compression (13). The external compression increases the intro-abdominal pressure encouraging fluid uptake through contra-lateral lymphatic pathways, especially when the diaphragmatic pump in the form of deep breathing exercises is utilized. External compression is recommended for patients with malignant ascites while it is contraindicated in cases of cirrhotic ascites.

DIALYTIC ULTRAFILTRATION/REINFUSION

This method is used only in cases of cirrhotic ascites. Essentially, the computerized unit:

1. Removes water and other ineffective molecules from the ascitic fluid

2. Concentrates ascitic fluid proteins and re-infuses them back into the general circulation or the peritoneum

3. Filters toxins and enhances ascitic content with immunologically active cells to decrease the risk of infection (7)

It seems to be completely free of any adverse side-effects (1), yet has not been widely reported as useful in hospice and palliative care settings in North America, primarily due to cost.

If this method becomes widely accepted, cost effective and proven safer than paracentesis in a variety of cirrhotic situations, it could become the standard of care for ascites caused by liver dysfunction.

In Part II of this article in the next issue of JMS we will discuss application of Manual Lymph Drainage therapy as an additional tool to manage ascites.

REFERENCES

1. Badalamenti S. (1992). Treatment of refractory ascites: is dialytic ultrafiltration better than paracentesis? Hepatology, Vol 15 (2), 356-357.

2. Doyle D, ed. (1998). Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

3. Dudley F. (1992). Pathophysiology of ascites formation. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America, Vol 21 (1), 215-230.

4. Gines P, Arroyo V, Rodes J. (1989). Treatment of ascites and renal failure in cirrhosis. Bailliere’s Clinical Gastroenterology, Vol 3 (1), 165-185.

5. Gines P, Arroyo V, Quintero E, et al. Comparison of paracentesis and diuretics in the treatment of cirrhotics with tense ascites. Gastroenterology, Vol 93, 234-241.

6. Heckman C., Lawler P., Walczak J. Fluid imbalances: focus on ascites and effusions-a continuing education program. Cancer Symptom Management, Second Edition. Website: CancerSource.com.

7. Lai K. (1993). Dialytic ultrafiltration-an alternative treatment modality of cirrhotic ascites? International Journal Artifical Organs, Vol 16 (4), 177-179.

8. Loggie B, Perini M, Fleming R, et al. (1997). Treatment and prevention of malignant ascites associated with disseminated intraperitoneal malignancies by aggressive combined-modality therapy. The American Surgeon, Vol 63 (2), 137-142.

9. Moore KP, Aithal GP. (2006). Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. GUT, Vol 55, 1-12.

10. Moskovitz M. (1990). The peritoneovenous shunt: expectations and reality. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, Vol 85 (8), 917-927.

11. Olszewski W. (1991). Lymph stasis: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Boca Raton, USA: CRC Press.

12. Po C, Bloom E, Mischler L. (1996). Home ascites drainage using a permanent tenckhoff catheter. A Paper Presented at the Annual Conference of Peritoneal Dialysis. Website: Advances in Peritoneal Dialysis.

13. Preston N. (1995). New strategies for the management of malignant ascites. European Journal of Cancer Care, Vol 4, 178-183.

14. Rakel R, ed. (1998). Conn’s current therapy. Philadelphia, USA: W.B. Saunders Company.

15. Rosenberg S. (2006). Palliation of malignant ascites. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America, Vol 35, 189-199.

16. Sanyal A, Genning C, Reddy K. (2003). The North American study for the treatment of refractory ascites. Gastroenterology, Vol 124, 634-641.

17. Shah R, Spears J. (2002) Ascites. eMedicine. Accessed December 3, 2004. www.emedicine.com/med/topic173.htm

18. Williams A. (2005) Understanding and managing lymphedema in people with advanced cancer. JCN Online Journal, Vol 19 (1). PTM Publishers Limited.

John Mramor is the Therapist for Crossroads Hospice in Cleveland, Ohio. He specializes in massage and energy interventions, biodynamic craniosacral therapy and manual lymph drainage/compression therapy. He has been practicing for 16 years, formerly for the Hospice of the Visiting Nurse Association and prior to that, Malachi House, both in Cleveland. He follows patients throughout their disease progression, up to and including the moment of death. He is married to Betty and has three cats.

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: Issue #1 2015