Dear reader,

This part of our journal is dedicated to the medical aspects of massage therapy. For those of you who would like to extend your practice into this exciting field of massage therapy the information published by our authors here will provide priceless guidance. Everything you will read here is based strictly on the MEDICAL MASSAGE PROTOCOLs developed in tested in the clinical setting by leading world scientists of the manual therapy and medical massage.

Medical Massage Concept

by Dr. Ross Turchaninov, MD

The latest trend in American medicine is the concept of integrative medicine in which traditional and alternative approaches are brought together for the patient’s optimal health benefits. In such a case, the ultimate solution to an illness finds itself in the flexible combination of different methods and techniques whereby the physician approaches the abnormality from different perspectives.

This concept, however, will never be as effective as intended so long as pathological abnormalities in the soft tissue remain unaddressed. Modern medicine has one tool alone that can accomplish this quickly and efficiently: medical massage therapy. Let’s review how science sees the place of massage therapy in medicine of the 21st century.

The Western school of massage therapy is constituted of three equally important branches: preventive massage therapy or Therapeutic Massage (TM), Medical Massage (MM) therapy, and Sports Massage (SM). We will concentrate on the first two. The preventive role of massage therapy is a critical component in the maintenance of our health. The major medical benefit of regular stress-reducing massage sessions is a balance between the activity of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems which control the basic functions of our body.

According to the Stress Theory, developed in the 1930s by Professor G. Selie, MD of France, chronic stress is the initial trigger in the disturbing of the balance between both divisions of the autonomic nervous system, and is the first step in the development of chronic somatic and visceral disorders. As soon as this balance is disturbed, pathological changes in the function of organs and tissue start to change. For some time, the body is able to compensate for this deficiency and we do not feel any uncomfortable sensations. As soon as the compensatory period is over, however, the first symptoms appear.

Let’s look at this issue closer using two examples: one person has stiffness in the lower back in the mornings while another person feels uncomfortable sensations in the upper abdomen after consuming fatty and fried food. Usually we do not pay attention to such “mild” disturbances, but sooner or later, morning stiffness becomes acute lower back pain (i.e., Lumbalgia), and uncomfortable sensations in the upper abdomen are diagnosed as Gastritis. At this point, the critical window of prevention is past, and only treatment options remain. In both cases, if, during the compensatory phase, the patients had gone through the regular application of full-body TM sessions (in combination with a proper diet in the case of the potential Gastritis or exercise in the case of potential Lumbalgia), both abnormalities could have been prevented from blowing up into major health problems. There is no substitute for the preventive power of TM.

If we will continue to consider both patients with the now-diagnosed cases of Lumbalgia and Gastritis, we will find that the application of TM as a treatment option has limited clinical impact. The best-case scenario in the case of the Lumbalgia is a temporary decrease in the intensity of the symptoms owing to a transferring of the active trigger points in the lower back muscles into a latent or “sleeping” condition. The best clinical outcome of TM in the case of the Gastritis will be a decrease in anxiety and stress.

Thus, as soon as somatic or visceral illness has progressed past the point where the body is still able to compensate for the abnormality, TM alone does not provide stable clinical results. It is at this point that MM should be employed, and the medical massage practitioner being in a position to bring dramatic changes to the lives of patients with Lumbalgia and Chronic Gastritis.

What is Medical Massage (MM)? At one time, MM was part of American medicine. American scientists made great contributions to the fields of MM and manual medicine between 1940 and 1950. The names of Professor I. Korr, MD and F.L. Mitchell, DO are mentioned in many scientific and educational texts on medical massage and manual therapy published in all major Western countries. Despite the fact that the works of both scientists are greatly admired by medical and massage communities the world over, these groundbreaking authors and their works are rarely cited in their own land.

Currently, the term ‘medical massage’ is becoming more and more common among massage practitioners. There are seminars and classes offered, but in the majority of cases MM is misunderstood or even misrepresented. Since there is no legal body which controls MM issues or establishes professional standards, the only option left is to look at what international science tells us about MM.

A major misunderstanding which we have encountered many times is the assumption that there exists some special procedure, technique or method which is called “Medical Massage”; and there is always a book, DVD or seminar that will be offered to teach this particular method. However, a deeper look into the science of massage reveals that such an assumption in incorrect. For MM is in fact not a single method or technique, but rather a concept (Glezer, Dalicho, 1955). This concept brings together clinically tested massage methods and techniques developed by scientists during the 20th century in different countries including the U.S.

MM is based on a repertory of 7 basic massage techniques. The critical differences between the various ‘MEDICAL MASSAGE PROTOCOLs, as they are called, relate to where, how, when, in what combination these techniques are to be applied during any given MM session addressing a particular problem.

MM protocols are priceless tools for massage practitioners, for they are the result of decades of experimental and clinical studies conducted by physicians in all major Western countries. These protocols are established, tried and tested, and the practitioner need only learn them well and apply them appropriately.

Since its beginnings, the concept of MM has been based on two major principles:

1. The practitioner must be aware of the source of the innervation of the soft tissue he or she is working with

The medical massage practitioner must consider this important information because the optimal therapeutic impact of the treatment can only be achieved if the local and reflex mechanisms of massage are combined for the client’s health benefits. By knowing the source of innervation, the pathway of the peripheral nerve which supports the affected area, and the effect of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems on this area, the massage practitioner can choose the correct combination of massage techniques and engage the patient’s nervous system into a healing process, creating a massage protocol unique to each client’s presenting situation. Use of the reflex mechanism of the massage therapy greatly increases the clinical effectiveness of the MEDICAL MASSAGE PROTOCOL employed.

2. All methods and techniques applied within the affected area must address the soft tissue layer by layer

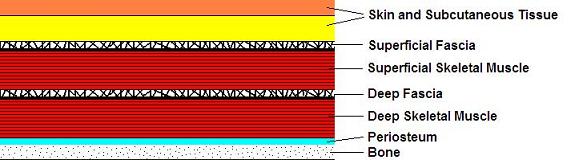

Let’s look at the most common arrangement of soft tissues encountered on the human body. There are 6 layers of soft tissue: skin and subcutaneous fat; superficial fascia; superficial muscles; deep fascia; deep muscles; and periosteum (see Fig. 1). The periosteum is a connective tissue membrane which covers all bones and is the place to which all soft tissues are anchored.

The technical application of MM demands a layer-by-layer approach using special methods or techniques that have been developed for each type of soft tissue.

To address the skin, the practitioner may use superficial effleurage, superficial friction, kneading of the fold of skin, and connective tissue massage. The best techniques to address superficial fascia are connective tissue massage and myofascial release. The superficial and deep muscular groups should be treated with trigger point therapy, postisometric muscular relaxation and myofascial release. To address the deep fascia, the practitioner may use connective tissue massage as well as kneading of the superficial muscular group applied in the inhibitory regime. The best way to address the periosteum is through the application of periostal massage and Cyriax’s friction.

Thus, each type of soft tissue, on each separate layer, calls for its own technical approach. This is the major difference between on the one hand MM, and, on the other, TM used for medical purposes. To use a military analogy, the application of TM for medical purposes is an example of carpet bombing, whereby the practitioner works on all tissues in the affected area in the hopes of, in the process, hitting the target. By contrast, MM is comparable to a precisely aimed guided missile.

When a scientifically designed MM protocol is used, the practitioner should know precisely where he or she is, what he or she is targeting at any given moment, what the subsequent step will be, and what is the expected outcome of the particular session as well as the treatment in general. This is the beauty of MM protocols.

In a sense, MM is like an overarching concept encompassing only scientifically designed and clinically tested methods and techniques. Basing itself on scientific publications, the modern concept of MM recognizes and makes use of the following methods of treatment:

1. SEGMENT-REFLEX MASSAGE (SRM)

SRM is the first method of MM to have been developed. In 1936, Professor A. E. Sherbak, MD, of Russia formulated the general concept, and in 1955, Dr. O. Glezer and Dr. V.A. Dalicho (1955) of Germany perfected the diagnostic procedure and therapeutic protocols. SRM is the most integrative method of medical massage because it addresses all types of soft tissues during a single session. A similar approach is used only by Neuromuscular Therapy.

2. CONNECTIVE TISSUE MASSAGE (CTM)

CTM was developed by physical therapists E. Dickle (1979) and Professor W. Kohlrausch MD, (1953) from Austria. CTM targets skin, fascia and aponeurosis.

3. PERIOSTAL MASSAGE (PM)

PM was developed by two German physicians, Dr. P. Vogler, MD, and Dr. H. Krauss, MD, (1953). PM targets pathological changes in the periosteum.

4. NEUROMUSCULAR THERAPY (NMT)

The basic concept of NMT was developed by S. Leaf, but it is Dr. L. Chaitow, DO, (1984), of the United Kingdom who must be credited for the modern NMT protocols.

5. MYOFASCIAL RELEASE (MR)

MR was developed in the USA by Barnes, PT (1990). The primary target of MR is connective tissue structures, with skeletal muscles being affected secondarily.

6. POSTISOMETRIC MUSCULAR RELAXATION (PIR)

The brilliant idea of American physician F.L. Mitchell, DO, (1948) was further developed by his son Dr. F.L. Mitchell Jr. (1995) and Dr. K. Lewit, MD (1997), and Dr. V. Janda, MD (1979) of the Czech Republic. The combination of trigger point therapy and PIR is the most effective way to quickly and efficiently eliminate hypertonus and trigger points in the skeletal muscles.

7. ROLFING (RF)

RF was developed by I. Rolf (1989), who based her method on the concept of osteopathic medicine. RF targets skin, connective tissue, and the superficial layer of muscles.

8. CYRIAX’S PROCEDURE (CP)

CP was developed by J. Cyriax, MD (1985) of the United Kingdom. This method targets the tendons and ligaments around major joints. The combining of CP and PM is most effective in quickly and efficiently eliminating pathological abnormalities in the periosteum (e.g., Tennis Elbow).

9. STRETCHING MASSAGE (SM)

SM was developed by Russian physician A. Manakov, MD (Flerova, 1955), and it is applied in cases of contractures in the major joints and peripheral vascular disorders.

10. VIBRATION MASSAGE (VM)

The basic concept of VM was developed by G. Taylor, MD (1879) and Snow, MD (1917) in the U.S. Professor Ya. Kreimer, MD (1989) from Russia developed MEDICAL MASSAGE PROTOCOLs for VM basing his recommendations on extensive experimental and clinical studies conducted at the Neurology Department of the Tomsk Medical School.

The primary goal of VM is the patient’s central nervous system. For the practitioner, the correct application of VM is a therapeutic tool of great clinical importance. It allows the practitioner to control the patient’s pain-analyzing system and can be made to have either a stimulating or an inhibiting impact on the local activity of the autonomic nervous system.

11. LYMPH-DRAINAGE MASSAGE (LDM)

LDM was developed by French physical therapist E. Vodder (1936). LDM is the best treatment option for addressing peripheral and post-traumatic edema. LDM is also the first critical step in the application of visceral massage.

12. VISCERAL MASSAGE (VMS)

VMS is used in cases of inner organ disorders in the abdominal and pelvic cavities. Because VMS has a local therapeutic impact it should always be combined with massage methods that have a reflex effect upon the function of the inner organs: SRM, CTM, NMT (Loginova, 2000).

VMS as a local therapeutic procedure includes three equally important components (Bashnyak, 1993): preparation of the abdominal wall, application of LDM to increase venous and lymphatic drainage from the affected inner organ, and actual visceral manipulations.

Thus we have at our disposal 12 scientifically tested methods of MM. How can we define the term ‘medical massage practitioner’? C. M. Versagi in 2002 reported that one of the existing views defines medical massage as a regular Swedish massage session conducted in a hospital setting. If we agree with this assumption, then it should follow that a Swedish massage session conducted in a supermarket could be labeled “supermarket massage”. We think the reader will agree that this would be a condescending term to describe the Swedish massage procedure.

As mentioned above, MM is a concept. Accordingly, a medical massage practitioner is a person who has adequate training in several important MM methods and is aware of how best to target the methods and techniques he or she commands to the specific layers of the soft tissue requiring treatment. Only in such a case of solid know-how is the practitioner able to conceive and apply MM protocols relevant and unique to each client’s specific presenting soft-tissue pathology, as determined by knowledgeably conducted client interview and examination of the soft tissue.

Let’s assume that the massage practitioner has taken a class in and practices Lymphatic Drainage Massage. He or she will bring dramatic improvements to the health of patients suffering from peripheral edema and will stimulate the patient’s immune system. However, if he or she were to apply LDM in a case of Tennis Elbow, the clinical outcome of the treatment would be very limited and short-lived, as LDM, aside from its ability to reduce local edema, has a very small therapeutic impact upon pathological changes in the periosteum itself. On the other hand, the application of Periostal Massage would have been the best choice of therapy given that PM has been designed precisely to address pathological changes in the periosteum. Thus, according to the concept of MM, the protocol of treatment should consist in methods and techniques specifically conceived to address specific pathological abnormalities in the soft tissue, rather than be a set method or technique, or a set combination of methods and techniques, which the practitioner applies indiscriminately over and over again — which, sadly, is all-too-often the case.

A surgeon does not conduct surgery by scalpel only; rather, he or she makes use of a whole set of surgical instruments. Similarly, MM methods and techniques are instruments, or tools, of the massage practitioner who practices MM. The more tools you have at your disposal, the more effective your MM protocols can be expected to be.

Unfortunately, however, today’s reality in the field of American massage therapy does not reflect this ideal of versatility. For while traditional medicine is moving increasingly in the direction of greater and greater integration, massage therapy is moving in the opposite direction, that of fragmentation. There are trigger point therapists, active stretching specialists, myofascial release practitioners, connective tissue massage therapists, etc., most of whom stay within the application of one method or technique.

All these methods are great and effective techniques and approaches, but they are simply tools and are therefore less effective when used alone. If the practitioner wants to become clinically effective, he or she must go beyond the boundaries of a single method or technique practiced on all clients without any individual approach or selectiveness. This is why MM is the most integrative concept of massage therapy, and the most intriguing and rewarding to learn and practice.

The methods and techniques mentioned above are components of the MM session which the practitioner is to use according to the type and pattern of abnormality in the soft tissue. However, basic TM remains an important part of every MM session. It is the frame, or “glue,” which holds all MM methods and techniques together and creates a perfectly orchestrated MM session. That is, there is no need to presume, as a prospective practitioner of MM, that you need to abandon and replace the TM massage routines you have enjoyed conducting up until now, which you have made your own and which may be a unique (and highly appreciated) signature of your personality as a massage practitioner. The beauty of MM is just this, that it can be incorporated selectively into, and can enrich, a general TM routine.

The practitioner should thus begin the MM session with an introductory part comprised of TM within the borders of the affected area, should apply TM before the application of each new MM technique, and finally should conclude the session with the re-application of TM. The twelve methods and techniques mentioned above constitute a basic set of professional tools for the massage practitioner. It is to be hoped that the field of MM will remain in a dynamic state of growth, with the number of methods and techniques expanding as new and exciting approaches emerge. How is the profession to decide, though, whether a newly proposed method or technique warrants a place in the field?

There is a very simple criteria: Was the effectiveness of this method examined in at least one study where it was tested against a placebo (against a simple relaxation technique, for example)? If it was, and the results of the study were statistically convincing and were published in a peer-reviewed medical, physical therapy or massage journal, we have a new method or technique which can, and ought to, be promoted, studied and practiced. There is no other waythat a newly developed modality should come to find itself under the umbrella of MM.

We are perfectly aware of the voices of those critics who would hold that in a free market-driven society, everyone ought to be able to promote anything, and “Let the market decide.” A laxer standard such as this is fine in regards to stress reduction or therapeutic massage; there was no need for the creators of Hot Stone Massage, for instance, to subject their proposed modality to scientific evaluation, as this recently developed (and may we add, great) type of bodywork targets healthy individuals, where therapeutic outcome is not really an issue.

However, if the clinical benefits of MM are to be counted on, it must be subjected to the same rigorous standards of research and demonstration as any other medical procedure or approach.

For instance, cardiac bypass surgery is conducted in every cardiac hospital the world over according to a similar protocol, with any new additions to the protocol having gone through vigorous testing first. Since the massage practitioner is also trying to affect a pathological condition, the same standard must be applied to the development of new methods of MM. New MM modalities should not be endorsed, promoted and studied based solely on an author’s claims of their effectiveness, and in the absence of a solid scientific foundation.

MM has its origins within traditional medicine, and sooner or later will be recognized in the as a legitimate and effective mode of treatment. However, one cannot expect proponents of traditional medicine to all of a sudden appreciate the clinical benefits of MM and to promote it.

Appreciation of MM within the medical community can only occur if massage therapists take the initiative of exposing local physicians to the proven benefits of MM via published scientific data rather than anecdotal reports, at the same time as obtaining, and being seen to obtain, real clinical improvements in, or even complete resolution of, patients’ illnesses.

REFERENCESBarnes, J.F. Myofascial Release. “Rehabilitation Services, Inc.”, 1990

Bashnyak, V.V. Manual Therapy for Abdomen. “Nadstirya”, Lutsk, 1993

Chaitow, L. Neuro-Muscular Technique: A Practitioner’s Guide to Soft Tissue Manipulation. “Harpencollins”, 1984

Cyrax, J. Theory and Practice of Massage. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, Vol. 2. 11th Edition, Bailliere & Tindall, Toronto, 1985.

Dickle, E., Schliack, H., Wolff, A. Bidegewebsmassage, Stuttgart, 1979.

Flerova, S.A. V.A. Manakov’s System of Medical Massage. Medgiz, Moscow, 1956.

Glezer, O., Dalicho, V.A. Segmentmassage. Leipzig, 1955.

Janda,V. “Die muskularen Huptsyndrome bei Vertebragenen Beschwerden,” inTheoretische Fortschritte und Practische Erfahrungen der Manuellen Medizin, ed. by Neumann H.D. and Wolff H.D., Buhl, Konkordia, 1979.

Kohlrausch, W. “Der Verlauf der Reflektorischen Zones in Haut, Unterhant und Muskulatur.” Arch. Phys., 5, 1953.

Lewit, K. Manual Therapy For Medical Rehabilitation. Vinnitza Medical University, Vinnitza, 1997.

Loginova, L.N, Encyclopedia of Massage. “Ripol Classic”, Moscow, 2000

Mitchell, F.L. Sr. “The Balanced Pelvis and Its Relationship to Reflexes.” Academy of Osteopathy Yearbook, 146-151, 1948.

Mitchell, F.L. Jr., Mitchell P.K.G. The Muscle Energy Manual. MET Press, East Lansing, 1995.

Rolf, I. Rolfing: Reestablishing the natural Alignment and Structural Integration of the Human Body for Vitality and Well-Being. “Healing Art Press”, 1989.

Selie, G. Perspective in Stress Research. Therapies in Biology and Medicine, Vol. II(4), 1959.

Sherbak, A.E. The Physiological Effect of Reflex Massage. Medgiz, Moscow, 1936.

Snow, M.L. Mechanical Vibration. Its Physiological Application in Therapeutics.New York, 1917

Taylor G.H. Health for Women: Showing the Causes of Feebleness and the Local Disease Arising Therefrom; with Full Directions for Self-treatment by Special Exercises. American Book Exchange, New York, 1879.

Versagi, C.M. A House Divided. The Medical Massage vs Relaxation Massage debate. Massage, Nov-Dec: 108-119; 2002

Vodder, E. Le drainage Lymphatique, une nouvelle methode therapeutique. Sante pour tous, 1936.

Vogler, P., Krauss, H. Periostbehandlung. Leipzig, 1953.

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: Journal of Massage Science 2009 #1, Science of Medical Massage