by Kiera Nagle, MA, LMT

I believe massage therapy has a ripple effect – a radiating energy, an extension of our clients’ own healing processes, on through to the other humans within their circle. In work with pregnant clients, this connection is even more obvious, and infinitely rewarding.

When we work with a woman who is carrying another human inside her, we are essentially working with two people simultaneously. As practitioners of touch therapy, we must be fully present to be mindful of that fact. Part of our role as therapists is to educate our clients (and other health care practitioners) about the many benefits that purposeful bodywork engenders for both the mother and the baby. This work is both energetic and scientific. In this article, I will focus on the scientific aspects of the changes in the body of a pregnant woman, and how we can address those through manual therapy.

For all of our clients, stress can contribute to, and exacerbate, a variety of physical and emotional conditions in the body. In general, massage can reduce stress in the body by decreasing muscular tension, releasing pressure built up in the fascia, increasing circulation, supporting respiration, and enhancing overall parasympathetic nervous system response: relaxation. These effects are especially important for pregnant clients, as the rapid and profound physiological changes they experience produces stress and anxiety, in addition to having a major impact on all the body’s systems.

Currently there is an abundance of research available that supports the efficacy of massage for the treatment of pregnancy-related symptoms, postpartum depression, and enhancing infant’s development. Much of this research has been conducted at Touch Research Institute at the University of Miami School of Medicine, led by its Director – Tiffany Field, PhD.

Numerous studies have shown that stress during pregnancy can result in low birth weight, premature labor, fetal hypoxia and the infant’s delayed neuro-motor development. Negative effects of stress on the mother reduce the effectiveness of oxytocin, resulting in a slowed labor process that may lead to obstetrical complications and medical interventions.

Mothers may also have an elevated heart rate, higher blood pressure and a higher incidence of miscarriage if they are experiencing continuous stress throughout their pregnancies. They are also more likely to be diagnosed with post-partum depression after delivery.

Dr. Field’s (Field et al.,1996) and others’ research supports that aside from the many massage benefits for pregnant women and postpartum mothers, premature infants who receive massage in NICU exhibit greater weight gain, show lower pain responses on the PIPP scale, have shorter stays in the hospital, as well as better Bayley Scores (Abdallah et al., 2013).

Other studies show that massage strengthens the attachment bond between mothers and infants (Gural and Polat, 2012), as well as enhances father-infant interactions (Cullen, et al., 2000). Parents are more likely to massage their infants if they are regular recipients of massage themselves. If they are not already massage regulars, pregnant women and their spouses can use this time in their lives to experience massage as a therapy.

Prenatal massage can address specific symptoms unique to pregnancy. A beneficial prenatal massage session should be well planned in order to address the client’s goals for the session. It is important as well to provide a holistic, whole-body treatment that addresses the variety of discomforts that she may be experiencing.

The typical treatment should be at least 60 minutes, in side-lying position for the entirety, split 35/left and 25/right, or by shortening the side-lying timing and allowing for 10-15 minutes of supported semi-reclining position (also known as the constructive rest position) at the end of the session, or 10-15 minutes of prone work using the pregnancy pillow system at the start of the session. Fig. 1 illustrates typical side-lying position.

Fig. 1. Side-lying position during massage session

This timing and positioning allows the therapist to address neck and shoulder tension, which may be contributing to headaches or discomfort, as well as what is likely the main complaint: low back pain and strain. Therapists can use a variety of techniques, such as Myofascial Release, Trigger Point Therapy and Swedish Massage techniques, on the muscles of the neck, back, limbs, gluteal region, as well as in the abdominal area, in order to fully address the client’s discomforts. Acupressure, and various Eastern techniques can be also incorporated into the massage session.

For most pregnant clients, the chief complaint during the 2nd and 3rd trimesters of pregnancy will be musculoskeletal pain. By decreasing chronic muscle tension, Pregnancy Massage helps to restore the client’s postural balance and reduce muscle pain. The current recommended weight gain for a woman of average height, weight, and BMI during pregnancy is 25-35 lbs. Even if the client stays within the normal range, she still has increased weight, mostly localized in the middle section of the body on its anterior surface. This triggers the increase in lordotic curve and an anterior pelvic tilt. Many factors, such as the anterolateral expansion of the ribcage 2-3 inches, can further exaggerate the lumbar lordosis.

Weakness of the abdominal muscles can result in diastasis recti or separation of the abdominal muscles. A properly trained therapists should teach pregnant clients to do isometric exercises to strengthen the abdominal muscles, in order to reduce the possibility of this separation and other postural shifts.

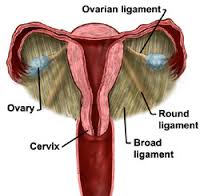

Another factor that may contribute to various pain patterns is the strain that the growing uterus places on the uterine and pelvic ligaments. Fig. 2 illustrates the ligamental support of the uterus.

Fig. 2. Anatomy of broad and round ligaments of the uterus

The strain of the broad uterine ligaments presents a clinical picture similar to sciatic pain and piriformis syndrome. The therapist should address this problem by working in the gluteal region and by carefully applying direct pressure to the piriformis muscle. This treatment becomes even more effective if the client is simultaneously stretches and straightens her leg. The intensity of pressure must be in the client’s comfort zone.

Strain on the round ligaments can be felt as pain in the anterior groin and thigh. This issue must be addressed with clients in the side-lying position while the therapist performs light stripping along the pelvic ridge. If the client’s body responds with resistance to this work, the therapist may stretch the fascia in the opposite direction using mini-myofascial release. Another option is light cross-fiber friction to the hip adductors with the client in the semi-reclining position.

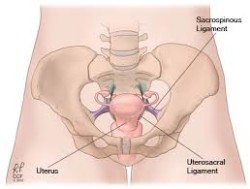

Strain on the utero-sacral ligaments may result in dull sacral pain and lower back pain (see Fig. 3). These symptoms should be addressed by encouraging the client to tuck her tailbone in, while the therapist puts moderate pressure on the sacrum, as the client is in the side-lying position.

Fig. 3. Anatomy of utero-sacral ligaments

During pregnancy, women experience an increased blood volume up to 30-50%. There is an increased chance for clotting especially in the venous system of the lower extremities, due to the increased in blood volume along with the concurrent decrease in activity of the anti-coagulant system. In addition, by the 3rd trimester, there is an approximately 40% increase in the accumulation of interstitial fluid throughout the body as well. As a result of the significant increase in the volume of circulated fluids, as well as fluid retention, clients may experience peripheral edemas.

Considering these facts, it is recommended that any massage strokes should follow basic rules of Manual Lymph Drainage: strokes must be lighter, directed upward, and performed in proximal-distal-proximal sequence. The stimulation of venous blood and lymph circulation helps to expedite the delivery of nutrients to tissues, and enhances the waste elimination process. This also contributes to a reduction of swelling and supports a healthy in-utero environment.

Due to the anterolateral expansion of the ribcage, exacerbated by pressure on the diaphragm from the growing uterus, the pregnant client experiences an increase in respiration efforts, and shortness of breath. The incorporation of breath work into the session, and massage techniques that target the respiratory muscles assists the client to breathe more deeply, which in turn delivers more oxygen to the fetus.

From the Eastern Medicine perspective, the therapists need to be aware of the benefits and contraindications of acupressure therapy during pregnancy. This therapy can be used to additionally enhance Western techniques and to formulate an integrative approach to the therapy. Elaine Stillerman, in her highly recommended book, Prenatal Massage: A Textbook of Pregnancy, Labor, and Postpartum Bodywork provides a combination of points to address various discomforts of pregnancy. This is a fabulous guide, though many therapists who are not already using acupressure may feel the need to review point locations prior to incorporating this work into the therapy. The therapists should be aware about the location of points that are contraindicated for the pregnant client. However, these same points can be very useful later when it is time to encourage labor.

Acupressure is a very useful tool to treat pregnancy side effects like nausea and vomiting (Werntoft and Dykes, 2001). The therapist may also teach the client to use self acupressure to control nausea.

Aside from the contraindications for acupressure, there are other contraindications the therapists should be aware of when working with pregnant clients. In the first trimester, and throughout the pregnancy, do not apply deep pressure to the abdomen. The work in the abdominal area, as the uterus expands, is a skillful blend of Myofascial Release and Swedish massage techniques which need to be learned from an experienced educator.

While some practitioners work with the pregnancy pillow systems or pregnancy tables with recesses, long periods of prone work, in my opinion, are not recommended. If a therapist does have access to the pillow wedge system, which would be the preferred method for prone work, it should not exceed 10-15 minutes, and during that period the therapist needs to communicate with the client about her comfort level.

The tables with recesses are problematic because they do not allow for a range of body types and shapes. We know that some clients have longer or shorter torsos, pregnant or not. In addition, due to the increase in fluid volume in the body, there is a concern for the potential restriction of tissue and subsequent swelling especially in the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the abdomen. As a result of the client’s prone position on the stomach while her belly is in the table’s recess, the force of gravity pulls the interstitial fluid into the soft tissues of the abdomen, overloading part of the body which is already functioning under significant stress.

Therapists who cannot afford, or do not have access to the pillow system, should know that 2-4 strategically placed bed pillows give the client comfort in the side-lying position. In this position, working on the quadratus lumborum or the iliopsoas would be contraindicated, but the therapists can work on superficial gluteal muscles and piriformis, in addition to performing trigger point work around the scapulae.

On the upper body the therapist can use stripping and cross-fiber friction to the flexors and extensors of the forearm, on the levator scapulae and other small muscles. The applied pressure can be stronger while the work in the lumbar area and on lower extremities limbs tends to be lighter as we discussed earlier.

On the psychological/emotional level, the touch therapy during pregnancy helps women to increase awareness of their bodies, and deepen their connection to this human phenomenon. A closer and more positive relationship to body, and herself, fostered by the massage experience helps to prepare women physically, mentally, and emotionally for the labor. The therapists also should promote self and partner massages, for client “homework” or self-care.

An issue I would like to discuss separately is the value of Perineal Massage. As many studies have confirmed, the Perineal Massage conducted by women or their partners dramatically decreases the chances of episiotomy during the labor.

Episiotomy is an incision of the perineum (i.e., tissue between the vaginal opening and the anus) conducted by an obstetrician during childbirth to speed up the final part of labor. The therapist should teach this simple procedure to the woman or her partner. Perineal Massage can potentially save women from the episiotomy and the unpleasant healing process which follows. Avoiding episiotomy greatly speeds up the woman’s recovery after the labor and helps her early and full engagement with newborn.

As Labrecque, et. al., (2001) showed in their study, Perineal Massage conducted by women or their partners 5-10 minutes every day or every other day starting at the 35th week significantly decreases the chance of perineal trauma during childbirth. As the authors concluded, “…one case of perineal trauma requiring suturing was avoided for every 11 women without a previous vaginal birth who were assigned to the massage group.”

Through massage and other supportive modalities, the properly trained and experienced therapist enriches a woman’s perception of pregnancy and helps her to create positive associations between physical changes in her body and the surrounding environment. We as therapists must encourage our clients, sisters, significant others, and friends who are pregnant to take care of themselves during each stage of their pregnancies. New mothers who do so will likely find themselves in a better state to take care of their babies.

While in popular culture massage may still be perceived as a “treat,” a special or extraordinary experience, therapists must educate women to consider that integrative health care

is not pampering, and should never be seen as a luxury. When therapists are able to speak in the same language as the client’s other health care practitioners, and assure her of the safety of the methods, as well as the myriad benefits, she will embrace massage as an important modality to support her pregnancy.

Pregnancy is not a disease or an illness and should not be treated as such, but it is a special condition that requires a deeper knowledge of anatomy, physiology and applied techniques. I advocate that practitioners who work with prenatal clients do pursue continuing education in these areas. There are some cautions even with healthy pregnancies, and it is absolutely necessary to have a working knowledge of high-risk conditions. The training, however, is not only about what you shouldn’t do while working on a pregnant client. It also provides insight into the application of various methods and techniques, special positioning, etc., that can be used to address the various discomforts associated with pregnancy.

As a teacher, I am often asked a range of questions from both ends of a spectrum: those of a highly precautionary nature that fear working with prenatal clients out of concern for harm; and those on the other end who attempt to downplay or disregard some of the cautions that are indeed necessary to consider for massage during pregnancy. MaMassage® classes we offer to therapists address both ends of that spectrum and the range of content in between as well.

While I love every minute of this work, with each client and student, the most exalted moment occurs at the start and end of each session. In those primary and terminal moments of connection, there is an electric quality to the air around us. The therapist “joins forces” with the client and the tiny human inside her to form a circular trinity of energetic exchange in the therapeutic present. Sometimes there is a flutter beneath your hands; the baby acknowledging the warmth, or the touch. Sometimes you feel the client’s relief as she exhales, or her muscle release as she lets it go. It is awe-inspiring to hold space for them both as they weave together and heal themselves, from the outside in, and the inside out.

REFERENCES

1. Abdallah B, Badr LK, Hawwari M. The efficacy of massage on short and long term outcomes in preterm infants. Infant Behav Dev. 2013 Dec;36(4):662-9.

2. Cullen, C., Field, T., Escalona, A. & Hartshorn, K. Father-infant interactions are enhanced by massage therapy. Early Child Development and Care, 2000,164, 41-47.

3. Field, T., Grizzle, N., Scafidi, F., Abrams, S., & Richardson, S. Massage therapy for infants of depressed mothers. 1996 Infant Behavior and Development, 19, 109-114.

4. Gural A., Polat S. The Effects of Baby Massage on Attachment between Mother and their Infants. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2012 Mar;6(1):35-41.

5. Labrecque, M., Eason, E., Marcoux, S. Perineal massage in pregnancy. Such massage significantly decreases perineal trauma at birth. BMJ. 2001 Sep 29; 323(7315): 753.

6. Stillerman E. Prenatal Massage: A Textbook of Pregnancy, Labor, and Postpartum Bodywork. St. Louis, Missouri, Elsevier, Mosby, 2008

7. Werntoft, E., & Dykes, A.K. (2001). Effect of acupressure on nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. A randomized, placebo-controlled, pilot study. The Journal of Reproductive Medicine, 46, 835-839

Kiera Nagle, MA, LMT serves as faculty and clinical supervisor, as well as the Director of the Asian Holistic Health and Massage Program at Pacific College of Oriental Medicine-NY. She provided prenatal massage at University of Nebraska Medical Center in a groundbreaking integrative health partnership, and serves as Clinical Supervisor for Massage Therapy Interns at Katz’s Women’s Hospital at NSUH-LIJ. She’s the mother of an amazing five year old. Please visit her website: MaMassage.org for more information.

Category: Stress Reduction Massage