By Dr. Ross Turchaninov

In the previous issue of JMS we published Part I of this article where we discussed anatomy and physiology of Neuromuscular Junctions (NMJs) and their role in the formation of various hypertonic muscular abnormalities. Before reading Part II of this article we suggest to those readers who missed Part I read it by clicking on this link: https://www.scienceofmassage.com/2018/01/lets-talk-about-neuromuscular-junctions-part-i/

As readers learned from Part I the NMJs play a critical role in the normal functioning of skeletal muscles. At the same time any pathological changes in the soft tissues formed around NMJs greatly affect muscle function. In Part II we will discuss clinical locations of NMJs and evaluation of tension formed around them.

LOCATIONS OF NMJs

First of all, we need to determine the area of NMJ within the examined muscle. For the large muscles it is a relatively simple task. The motor nerve enters the muscle at the middle of the muscle belly and it connects skeletal muscle to the upper (in the cortex) and lower (in the spinal cord) motor centers in the CNS.

Exactly in the middle of the muscle belly the main NMJ is located and it is there electrical potentials which propagated along the spinal and peripheral nerves finally are converted into electrical disturbance within the muscle, which initiates full contraction.

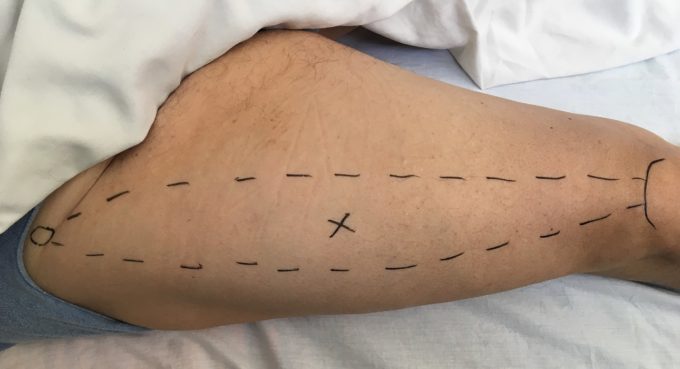

Each motor nerve when it gets in contact with muscle fibers splits on many small terminal branches which forms NMJs with a number of individual muscle fibers. However, all these NMJs are anatomically located in the same area of the muscle (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Axon and its terminal branches make NMJs with several muscle fibers (image made with electronic microscope)

Fig. 1. Axon and its terminal branches make NMJs with several muscle fibers (image made with electronic microscope)

1 – motor nerve

2 – Neuro-Muscular Junctions

3 – individual muscle fibers

The number of NMJs which are in contact with individual muscle fibers allow more balanced muscle contractions since there are no delays in the spread of the commands throughout the entire muscle belly.

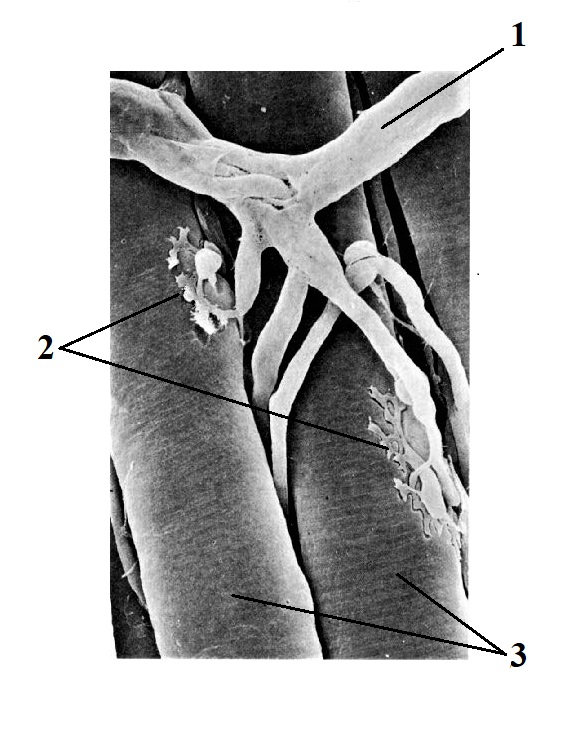

Thus, to examine the area of NMJ the therapist must examine tissue in the middle of the muscle belly. Despite its obvious simplicity, finding this area may present some challenges. If the muscle has very short tendinous attachments it is very simple to determine the area of NMJ. The therapist detects both bone structures of muscle origin and attachment, keeping in mind the anatomical direction of the fibers examining soft tissues around NMJs exactly in the middle of the muscle belly. Fig. 2 illustrates the find of NMJ in the rectus femoris muscle.

Fig. 2. Location of the NMJ in the rectus femoris muscle

Small circle – origin of rectus femoris at the anterior inferior iliac spine

Curved solid line – upper edge of the patella (insertion of quadriceps m.)

X-mark – area of NMJ in the middle of muscle belly in rectus femoris

Dashed lines – borders of rectus femoris muscle

However, the situation changes completely when muscle has long tendon. For example, the extensor digitorum muscle has a shorter belly and long tendons. Thus, the entire muscle starts from the lateral epicondyle and inserts into the dorsal surfaces of phalanges, but the actual muscle belly ends in the middle of the forearm. In such case NMJ for the extensor digitorum muscle will be located in the middle of its short belly. Fig. 3 illustrates the location of NMJ in the extensor digitorum muscle.

Fig. 3. Location of NMJ in the extensor digitorum muscle

Small upper circle – origin from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus

Dashed lines – borders of the extensor digitorum m.

X-mark – area of NMJ in the middle of muscle belly in extensor digitorum m.

Solid lines – tendons of extensor digitorum m.

Four small circles – insertions of tendons into the proximal phalanges

EVALUATION OF TENSION FORMED AROUND NMJs

There are two equally important aspects for the evaluation of NMJs: fascial tension and protective muscle tension.

Fascial Tension

Many different triggers may contribute to the increased tension within superficial and/or deep fascia. This very important subject requires separate discussion. We will consider that as a clinical fact and concentrate on the role fascial tension plays in the malfunctions of NMJs.

Superficial fascia covers superficially located muscles while deep fascia covers muscles located in the middle or deep layers of the soft tissues and it separates two muscle layers. The predominant orientation of the collagen fibers in fascia follows the direction of the muscle fibers it covers, and fascia stabilizes itself into the periosteum which covers all bones.

For each motor nerve to enter the muscle belly it needs to penetrate fascia first. Increased fascial tension is the main source of chronic, low grade irritation of the motor nerves. Such low- grade irritation is responsible for the muscle’s overreaction to even mild stimulation due to spontaneous release of acetylcholine as we discussed in Part I of this article. That becomes one of the main causes of eventual accumulation of chronic tension in skeletal muscles.

By testing fascia, the therapist can predict if the NMJ is under stress by fascial tension. To be informative, testing must be done in the area of NMJ and we discussed this topic above.

a. Superficial fascia

To test tension in the superficial fascia the therapist tests the mobility and elasticity of the skin. If tension builds up in the superficial fascia and as a result shortens the fibrotic bridges which hold skin and superficial fascia together, the skin becomes less elastic and ‘glued’ to the underlining fascia.

If such restrictions of skin elasticity and mobility detected in the area of the anatomical location of the NMJ, the therapist can be 100% sure when he or she considers that the motor nerve and NMJ it forms operates under the stress.

The videos below illustrate the tension in the superficial fascia developed as a result of chronic right side Lateral Epicondylitis (Tennis Elbow) in one of our patients. The superficial tension here covers the extensor digitorum muscle. Video 1 shows application of the Second Part of Kibler’s Technique (Kibler, 1958) on the unaffected upper forearm side, while Video 2 illustrates application of the same test on the affected side. In the second video (compared to Video!) the patient’s skin exhibits less elasticity while the fold is lifted due to the tension is superficial fascia.

In case of tension build up in deep fascia the sign of tension there will be restriction of the lateral shift between superficial and deeper layers of skeletal muscles. The next two videos illustrate examination of deep fascia which separates the extensor digitorum muscle from a deeply located supinator muscle. The Opposite Shift Technique is used to examine deep fascia in the same patient with chronic Tennis Elbow on the right side. The Video 3 illustrates testing of the deep fascia in the place of NMJ in the supinator muscle on the normal side of our patient with chronic Tennis Elbow and the Video 4 illustrates the same testing done on the affected side. Restriction of lateral shift is clearly visible in the Video 4 compared to the Video 3.

If during the testing of lateral shift of the superficially located muscle the therapist detects decreased mobility, it will be a direct indicator of tension built up in the deep fascia, irritation of the motor nerve and compression of NMJ which controls contraction/relaxation of the supinator muscle.

In both scenarios of the superficial and deep fascia testing the examiner should test the clinical picture on unaffected or less affected side first to be able to compare it with the affected area.

In Part III we will discuss treatment options to take pressure from the soft tissues around NMJ.

REFERENCE

Kibler M. Das Strorungsfeld bei Gelenkerkrankungen und inneren krankheiten. Hippokrates, Stuttgard, 1958

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: 2018 Issue #1