As our readers already know, JMS was pulled into a baseless discussion on the topic of the timing for Oncology Massage. Generally speaking, that discussion concerned the application of full body massages for cancer patients to reduce stress, anxiety and assist them through difficult times. This therapy promoted by T. Walton indeed is a very important job that many therapists around the country do daily to help cancer survivors.

However, there is another aspect of Oncology Massage which has very limited exposure among therapists while clinically speaking it has more importance. Oncology Massage Rehabilitation (OMR) is conducted by therapists as a member of a treatment team led by an oncologist who controls the patient’s entire rehabilitation. In these cases, OMR is an integrative part of the patient’s cancer treatment with predictable clinical outcomes.

There is a handful of therapists who are doing this difficult and very important job. I was very lucky to meet one of them, Vanessa Sifontes, during this year’s 34th Annual Convention of the National Association of Myofascial Trigger Point Therapists. For me personally, her presentation on the application of massage and manual therapy as part of treatment and rehabilitation of patients with head and neck cancer was the peak of the entire convention.

We were lucky that despite her very busy schedule Vanessa generously agreed to write a two-part article for JMS which is based on her presentation. We are sure that it will open the eyes of many therapists to the clinical possibilities of their profession in regard to cancer treatment using OMR.

Dr. Ross Turchaninov, Editor in Chief

ONCOLOGY MASSAGE REHABILITATION.

PART I: NEWEST SCIENTIFIC DATA, COMMONLY USED CANCER TREATMENTS AND THEIR SIDE EFFECTS

by Vanessa Sifontes, PORi Certified Oncology Rehabilitation Specialist

For many years the integration of massage and manual therapy techniques in the rehabilitation of oncology patients has been more than a taboo. Unfortunately, it has led to restriction in their clinical usage for rehabilitation of the soft tissues during and after cancer treatment.

I see four goals of this article:

1. Review modern research that demonstrates the importance of manual therapy techniques for cancer patients who undergo surgery, radiation and chemotherapy or their combinations.

2. Establishing some clinical guidelines for therapists to follow when they are working on cancer survivors who undergo radiation and chemotherapy to ease their negative impact on the soft tissues

3. Sharing clinical experiences from our clinic with other therapists

4. Advocate the use of manual therapy techniques in the rehabilitation of oncology patients

PATHWAY OF METASTASIS: LYMPHOGENOUS DISSEMINATION

Unfortunately, the view that lymphogenous dissemination being increased with any type of manual therapy is incorrect. Research supports the idea that massage and manual therapy are very beneficial for cancer patients and do not contribute to the spread of disease if the cancer undergoes proper treatment first. Thus, it should not be withheld from patients with even metastatic form of cancer (Foldi, 1998).

At the same time, the timing of such therapy is a critical component of patients’ rehabilitation and this issue is of dire importance. All massage and manual techniques must start ONLY after oncology treatment (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy) started not a day earlier. I will not partake in another debate on this subject since there are enough evidences in scientific literature to support the view on timing (Knox, 1922; Wu et al., 2010; Wang, et al., 2014).

Please note that this article addresses therapy conducted in our clinic once cancer related treatment has already ensued. The best way to avoid any confusion is to become part of the treatment team under the direct supervision of an oncologist who is responsible for the entire patient rehabilitation.

While each tumor cell has all the necessary requirements to metastasize and thrive in the new places, some cells do that while others do not. Ruitler et al., (2001) gave the following explanation of why some cancer cells have very low efficiency:

“This low efficiency may be a temporary absence of a suitable microenvironment once the tumor cells escape from this original tissue compartment.”

In other words, each cancer is unique to each patient and immune response to the cancer as well as the body’s metabolism are also very distinct. Thus, cancer cells can be dormant until special conditions for their sudden thriving develop. This is the unfortunate nature of cancer which sometimes comes back even after 20-30 years of cancer free life. Thus, if the periphery of the initial cancer area which has a tendency to shed off cancer cells first is under control by oncotherapy, just elevation of interstitial pressure (i.e., pressure between individual cells) via increase of lymphatic or venous drainage do not create conditions for the cancer metastasizing compared to the normally present interstitial pressure (Godette, 2006).

NEW DATA ABOUT TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT

As we know, each skeletal muscle is covered by superficial or deep fascia and together, they form so called myofascial tissue. The basic components of fascia are: cells (primarily fibroblasts), fibers (collagen, elastin, reticular) and so-called extracellular matrix (ECM) whose fluid component is referred to as ground substance. Ground substance is the viscous fluid that facilitates chemical and molecular exchanges between blood, lymph and cells. It is the most immediate environment of every tissue in the human body (Juhan, 2003).

David Lesondak in his most recent book (2018) refers to the ECM as a spider web. When one part of it is pressured, tightened or stretched by manual work, the other side of the spider web is affected as well.

Special cells called fibroblasts are responsible for synthesis and maintenance of ECM. When tissues are injured, some fibroblasts are turned into myofibroblasts which produce bioactive substances called cytokines. These substances initiate and further support the inflammatory response in the tissues (Butcher et al., 2009) which eventually activates the pain analyzing system via overstimulating the sympathetic nervous system.

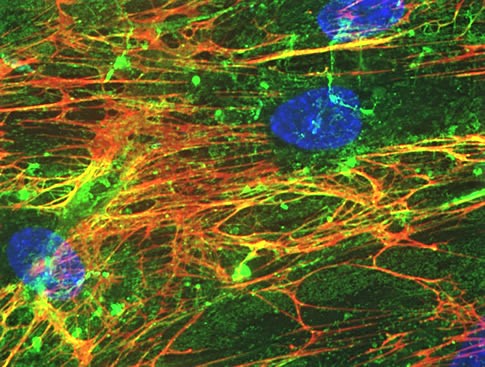

One of the most abundant components of ECM is a substance called hyaluronan. It is produced by recently discovered special cells called fasciacytes (Stecco et al., 2018) and hyaluronan lubricates the collagen and elastin fibers and thus it becomes the main lubricant for the entire fascia. The increase in hyaluronan’s viscosity is directly linked to the shortening of fascia and formation of secondarily hypertonic muscle abnormalities which results in Myofascial Pain (Stecco et al., 2011). Fig. 1 illustrates ECM with ground substance.

Fig. 1. Extracellular Matrix with ground substance (image Benaroya Research Institute)

Cells (blue nuclei) are surrounded by a network of extracellular matrix molecules:

– light green is hyaluronan

– red is fibronectin

Ground substance – dark green

Another very surprising function of ECM was recently discovered in its role in metastases formation and spread. We know that tumor spreads via lymphatic, circulatory systems or by invasion. However, what lets cancer cells escape the original tumor site? Why does tumor shed the cells and they metastasize in the first place? Until recently we didn’t have answers to these fundamental questions.

In 2014 exceptional study conducted by MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research (Naba et al, 2014) showed that the most aggressive metastatic tumors secrete certain proteins into the ECM and tumor uses these proteins as pathways through the ECM to help the cancer cells to escape and survive in new tissues located sometimes in very distant areas. Thus, the original tumor alters normal pressure within surrounding ECM and it creates easier paths for the cells which are ready to be shed to escape the original site and get into the lymphatic or circular system. This ground-breaking data has enormous potential for oncology in general and for everyone who practices ORM.

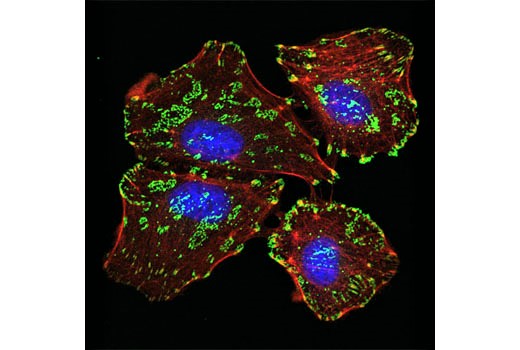

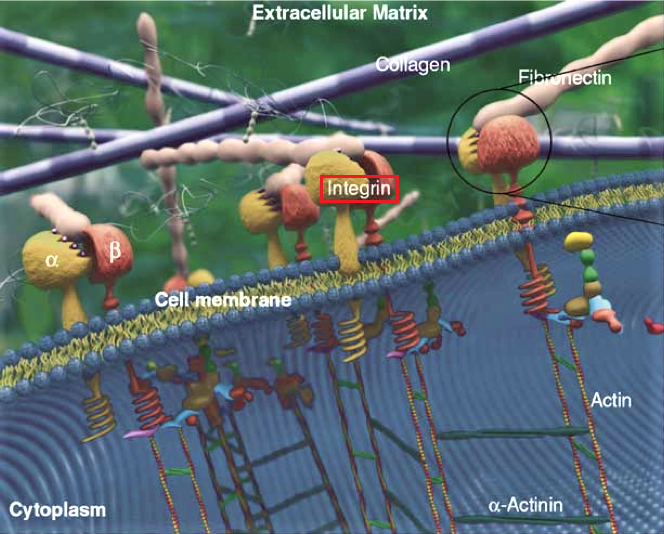

Now, I would like to briefly mention special receptors located on cell membranes called Integrins. They are purely mechanoreceptors which are activated only when any mechanical force is applied to the cell membrane. Also, these receptors are crucially important in holding each cell in its correct place within the ECM. I won’t go over this information again because the role of Integrins is discussed in detail in this issue of JMS in Dr. Turchaninov’s article in “Cellular Mechanisms of Massage Therapy. New Scientific Data.” Fig. 2 illustrates presence of integrin receptors on the surface of live cell.

Fig. 2. Integrin receptors (green colored) on the surface of the cell detected by Confocal immunofluorescent analysis (Image by Cell Signaling Technology)

As we know now the mechanical forces including massage strokes (Miller et al, 2018) elicited on the soft tissues affect cellular function and electro-chemical reactions within the tissues and first of all in the ECM. These changes affect cytoplasmic membrane activating integrins and they transform mechanical stimuli into different chemical and electrochemical reactions which trigger various processes within the cells and eventually stimulate their functions. Fig. 3 creates 3-d image of integrins embedded into the cellular membrane.

Fig. 3. 3-d image of integrin receptors embedded into the cellular membrane (image by Technische Universität Darmstadt Biologie)

However, the situation changes more dramatically in areas of injury or cancer. While the tumor is growing it increases pressure inside the ECM and ‘stiffens’ it, adhering individual cells while interfering with their functions (Leight, et al, 2012). Thus, rigidity of the ECM’s becomes one of the factors which changes the microenvironment in the cancer affected tissues and it contributes to further cancer growth, including its invasion and malignancy (Butcher et al., 2009). At the same time the tumor, as we discussed above, secretes proteins which in combination with stiffened ECM provides ideal conditions for the cancer cells to escape and metastases to form.

I would like to emphasize that all these events initially are the result of pure mechanical pressure changes in the area of cancer or injury due to interstitial edema or ECM stiffness. This issue is of great importance for therapists. Interstitial edema (i.e., accumulation of the fluid between the cells) in the area of cancer will additionally increase mechanical pressure on the ECM and integrins in the cellular membrane. In such cases decreasing the pressure in the tissue with manual work becomes a very important treatment option.

COMMON ONCOTHERAPIES AND THEIR EFFECTS ON SOFT TISSUE

Intervention in order to eradicate cancer ranges from Radiation Therapy (XRT) to Chemotherapy (CT) to Surgery. As my specialty and primary practice is dedicated to rehabilitation of Head and Neck Cancer (HNCA) patients, this is what I will use as a platform of reference as our discussion continues.

XRT Side Effects On Soft Tissues

XRT has been used successfully to treat cancer for many years. Despite of XRT’s effectiveness its side effects may affect the patients for years after treatment is completed and can be debilitating both physically and psychologically. For many years research within oncology and radiation experts has focused on diminishing the intensity and onset of side effects. This has included everything from finding the right dosage and means of delivery, to altering the schedule in hopes of reducing mortality while diminishing damaging side effects.

For our patients with HNCA radiation besides affecting head and neck soft tissues may damage even fascial bones. Mandible or maxilla often are irradiated during treatment of oral cancers, and it can damage bone fine vascular support. Normal bone marrow is then replaced with fatty marrow and fibrous connective tissue. Bone marrow becomes hypovascular and hypoxic, significantly affecting the degree of bone mineralization resulting in an osteoradionecrosis. If, this happens to the bone tissue, consider the profound impact XRT has on the Myofascial Tissue.

In addition, XRT side effects include mucositis (i.e., inflammation of mucous membranes in oral cavity), xerastomia (i.e., dryness in the mouth), alternation of taste, TMJ dysfunction, and secondarily skin changes (particularly radiation dermatitis that can be acute or chronic, that can lead to infection). Fig. 4 is an example of radiation dermatitis. (Please note all patient depictions have been authorized by patients themselves)

Fig. 4. Grade III Acute Radiation dermatitis, a week after the last XRT session.

One of the more permanent side effects of XRT is soft tissue fibrosis. Together with restriction in range of motions, and hypoxia (i.e. diminished tissue oxygenation) fibrosis dramatically increases ‘stiffness’ of the ECM and as we know now it plays an important role in overall malignancy, tumor invasion, and metastasis.

As professionals in manual therapy, we are familiar with the effects of hypoxia on soft tissue function, length, strength and hydration. Please remember that hypoxia makes cancer cells more aggressive. I would like to leave you with recent cell biology findings in regard to the hypoxia effect on ECM in cancer patients:

“Hypoxia has been shown to induce collagen deposition and modification of ECM proteins through induction of an array of enzymes…these findings suggest that a key effect for hypoxia in tumor metastasis is ECM remodeling, and potentially matrix stiffening” (Spencer et al., 2016).

I think the value of massage and manual therapy from this perspective has undeniable health benefits for cancer patients. Even gentle compressions of MLD in combination with careful tissue stretching and displacement dramatically decreases interstitial pressure within the tissue and fights with development of soft tissue fibrosis even in its early stages.

Chemotherapy Related Side Effects

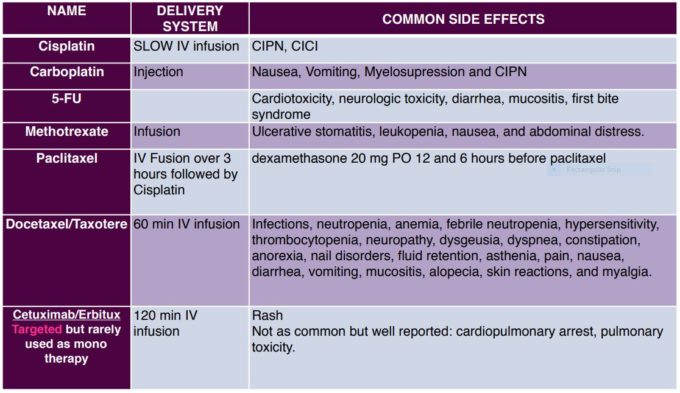

In the treatment of Head and Neck Cancer (HNCA), chemotherapy medications are prescribed based on their interference into the cancer cell lifecycle. Side effects include but are not limited to: myelosuppression, kidney damage (particularly with Cisplatin), cancer related fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, cachexia (i.e. losing weight), mild cognitive deficits as well as cardiotoxicity (with Taxanes and Erbitux).

In Table 1 you will find the most common chemotherapy drugs used in treating HNCA patients as well as their delivery system, and common side effects. Please note that most patients take a combination of three drugs compounding therefore the side effects of these.

Besides obvious side effects of chemotherapy like peripheral neuropathy and alopecia (hair loss), chemical residuals of medications called metabolites have the tendency to accumulate in the soft tissues especially in fascia and subcutaneous fat where circulation is poorest. Accumulation of metabolites in the fascia additionally contribute to its fibrosis and muscle tension developed secondarily. This is another important aspect of massage and manual therapy in cancer patients when the therapist addresses the fascia on different levels.

Side Effects Of Surgeries

There is a vast variety of head and neck cancers with different anatomical locations and different degrees of malignancy. Now add to that a very complex anatomical arrangement of the face and neck with a variety of vital structures there and it is obvious that head and neck surgeons have a very difficult job to take out as much cancer as possible while avoiding a variety of complications. I will not be able to cover all surgical procedures, but I will mention the most common one.

Modified Radical Neck Dissection (MRND)

As medicine has advanced the surgical removals of the cancerous tissue become less and less invasive and it gives better chances for reconstruction. When the neck cancer spreads extensively it invades muscles, lymph nodes, nerves, and blood vessels. A surgical incision is made along the most commonly affected lymph nodes to stop further progression of cancer.

In a patient who undergoes MRND, all lymph nodes level I (submandibular nodes) through level V (posterior triangle lymph nodes extending from mastoid process all the way down to the clavicle posterior to SCM) are removed. The surgeon sometimes faces the necessity of the accessory nerve dissection as well or the nerve is usually traumatized during the surgery. The internal jugular vein and sternocleidomastoid muscle are sometimes dissected as well, depending on the clinical case. Fig. 5 illustrates a postsurgical scar after MRND. Look at the location and extent of incision, consider the anatomy of this area and now imagine how it functionally affects a patient’s mobility and quality of life.

Fig. 5. Incision after Modified Radical Neck Dissection

Common sight 7-10 days post operatively. This incision is commonly referred as the “hockey stick” incision.

All patients exhibit different degrees of peripheral edema of the face and neck and wasting of the trapezius muscle if the accessory nerve was cut or muscle weakness in the nerve was traumatized. For these patients the timing of massage and manual therapy intervention is crucial since enhancement or restoration of proper drainage will prevent soft tissue fibrosis and ECM ‘stiffness’ while supporting the trapezius muscle’s functions.

Neck Reconstruction: Pectoralis Major Myocutaneous Pedicle Flap

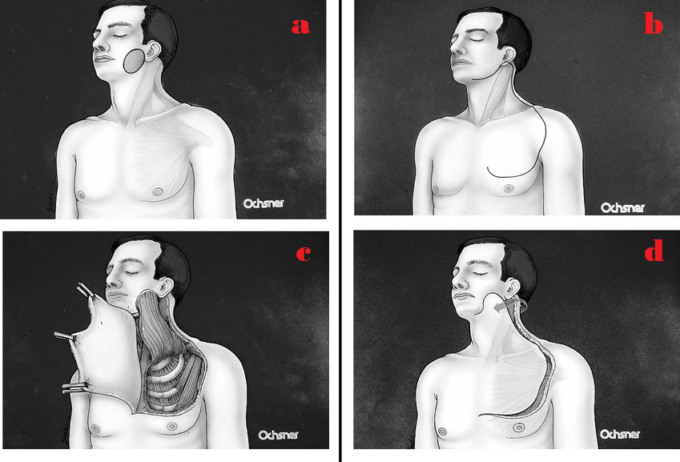

In my experience this is one of the most common and frequently performed head and neck surgeries. Flap Reconstruction is needed because after the surgeon removes all tissues affected by the cancer very frequently no soft tissue left and vital structures as arteries, veins, nerves, trachea, esophagus etc. directly exposed under the skin. They must be covered by the soft tissues. For this purpose, after removing the cancer, the second part of the surgery becomes soft tissue reconstruction. For this purpose, the surgeon uses part of the patient’s pectoralis major muscle to flip it on the neck to replace removed cervical soft tissues. Fig. 6 illustrates cervicopectoral pedicle flap surgery.

Fig. 6. Reconstruction of Lateral Facial Defects Utilizing the Cervicopectoral Rotation Flap (Anand et al. 2008)

Considering the amount of bulk of the soft tissues which need to be relocated, the patients usually exhibit significant mobility deficits, especially if surgery is followed by XRT and chemotherapy treatment which is the case in a majority of patients. Another negative aspect of Pedicle Flap surgery is a secondary compromise of blood supply and drainage to and from the flap because of the flap’s twist during re-location. Also, XRT and chemotherapy dramatically decrease the tissues’ ability to heal.

Patients after this surgery complain about everything from general fatigue to swallowing difficulties, edema, cervical and shoulder pain, tension and ROM restrictions. Fig. 7 illustrates the clinical case of a patient who has had a pec flap, followed by radiation.

Fig. 7. Patient from our clinic after Cervicopectoral Rotation Flap followed by radiation

As you see, the soft tissues are very fibrotic. Upon arrival to our clinic, the patient’s cervical ROM was severely limited, particularly when measuring cervical rotation to the right side which reached 25 degrees only with normal scale around 80 degrees.

In the second half of this article we will discuss the clinical impact manual therapy and massage have on the recovery of the soft tissues and how we may progress into an era when this important treatment tool becomes a key rehabilitative technique to minimize side effects and by doing so prevent cancer re-occurrence. I plan to share with readers case studies from our clinic describing exactly how manual therapy and massage have positively impacted patients, affecting their mobility and quality of life.

REFERENCES

Anand A.G, Amedee R.G., Butcher R.B. Reconstruction of Large Lateral Facial Defects Utilizing Variations of the Cervicopectoral Rotation Flap. 2008 The Ochsner Journal 8:186–190

Baum J. and Duffy H.S. (2011) Fibroblast And Myofibroblasts: What Are We Talking About? J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. April; 57 (4) 376-379.

Butcher D.T., Alliston T., Weaver V.M. A Tense Situation: Forcing Tumor Progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009; 9(2): 108-122.

Foldi E. The Treatment of Lymphedema. Cancer 1998; 83:2833-4.

Godette K.O., Mondry T.E. Can Manual Treatment of Lymphedema Promote Metastasis? J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006 Winter;4(1):8-12.

Juhan D. (2003) Job’s Body, 3rd edition. Barrytown, New York: Barrytown/Station Hill Press 5 Inc.

Knox L.C. The Relationship Of Massage To Metastasis In Malignant Tumors. Annals Of Surgery, Vol. LXXV Feb (2) 1922

Leight J.K., et al. Matrix Rigidity Regulates A Switch Between TGF-Betal Induced Apoptosis 13 And Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Mol Biol Cell. 2012; 23(5):781-79

Lesondak D. 2018. Fascia. What It Is And Why It Matters. Handspring Publishing, Edinburg

Miller B.F., Hamilton K.L., Majeed Z.R., Abshire S.M., Confides A.L., Hayek A.M., Hunt E.R., Shipman P., Peelor F.F. 3rd, Butterfield T.A., Dupont-Versteegden E.E. Enhanced Skeletal Muscle Regrowth And Remodeling In Massaged And Contralateral Non-Massaged Hindlimb. J Physiol. 2018 Jan 1;596(1):83-103

Naba, A., Clauser K.R., Lamar, J.M., Carr S.A., Hynes R.O. Extracellular Matrix Signatures Of Human Mammary Carcinoma Identify Novel Metastasis Promoters. eLife 2014;3: e01308

Ruicler O.J., van Krieken J.H., van Muijjen G.N., de Waal R.M. Tumor Metastasis: Is Tissue A Issue? Lancet Oncol 200I2: I 09-12.

Spencer C. Wei, King Yang. Forcing Through Tumor Metastasis: The Interplay Between 15 Tissue Rigidity And Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Trends Cell Biol. 2016

Stecco C, Fede C, Macchi V, Porzionato A, Petrelli L, Biz C, Stern R, De Caro R. The fasciacytes: A New Cell. Clin Devoted To Fascial Gliding Regulation. Anat. 2018 Jul;31(5):667-676

Stecco C, Stern R, Posizionato A et al. (2011) Hyaluronan Within Fascia In The Etiology Of Myofascia Pain. Surg Radiol Anat. December; 33 (10) 891-896.

Wang, J.Y., Wu, P.K., Chen, P.C., Yen, C.C., Hung, G.Y., Chen, C.F., Hung, S.C., Tsai, S.F., Liu, C.L., Chen, T.H., Chen, W.M. Manipulation Therapy Prior To Diagnosis Induced Primary Osteosarcoma Metastasis–From Clinical To Basic Research. PLoS One, 2014 May 7;9(5):e96571.

Wu P.K., Chen W.M., Lee O.K., Chen C.F., Huang C.K., Chen T.H. The Prognosis For Patients With Osteosarcoma Who Have Received Prior Manipulative Therapy. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2010 Nov; 92(11):1580-5.

Vanessa Sifontes is an Oncology Rehabilitation Specialist who has been involved in continuing education course planning and lecturing since 2014 when she first lectured in Houston, TX under TIRR Memorial Hermann. Vanessa at that time was responsible for program development of Post-concussion Syndrome and has continued with course development and education of fellow professionals and students every year since then. Of particular note, Vanessa was involved in Oncology Rehabilitation program development for Memorial Hermann TIRR in conjunction with UT physicians and was invited later to lecture with Dr. Ron Karni at the first MD Anderson Multidisciplinary Cancer Symposium.

In addition, just this year Vanessa collaborated on an article that was published in APTA’s Oncology Journal. Vanessa has demonstrated a continuous investment in education as a way of giving back to the community. She is consistently active in keeping up to date with research and participating not just in national associations concerning her field of practice, but also international and multidisciplinary affiliations such as being part of the European Head and Neck Society as well as Fascia Research Society. This is vital in staying up to date not only within her scope of practice, but within the scope of her desired specialty. Despite moving to Colorado, Vanessa did not abandon her licensure for the state of Texas, but instead is committed to continuing to be licensed in both states

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: 2019 Issue #1