By Dr. Ross Turchaninov

In Part I of this article, (Science of Massage Institute » SCIENCE OF MEDICAL MASSAGE THERAPY. Part I: Introduction to the Reflex Zones Concept) we had a general discussion of the reflex zones concept which is a critically important topic for everyone who practices any clinical aspects of massage therapy. We showed pictures of five patients with Trapezius Muscle Syndrome from our clinic and they all exhibited exactly the same clinical symptoms despite that the actual causes of the symptoms were completely different and they require a different approach to the therapy. It sounds confusing, but at the same time understanding and clinically implementing reflex zones the concept becomes the turning point in delivering relatively quick and stable clinical results of successful somatic rehabilitation.

Let us give the readers a quite simple example. 1 in 7 or 31 million Americans suffer from Migraine and Severe Headache (Burch et al., 2015). In the USA patients visit the with Severe Headache or Migraine every 10 seconds! At the same time there are countless publications and continuing education classes which promise therapists successful treatments for headache and migraines. Following the logic, if all suggested therapies are clinically sound why do patients with debilitating headache or migraine enters ER every 10 seconds? We are not even talking about millions of headache patients who stay and suffer at home. The answer is simple, the concept of reflex zones formation in the soft tissues has minimal exposure within massage therapy and physical therapy communities, despite that this concept is the cornerstone of the entire osteopathic medicine.

As long as the therapist is able to reconstruct in their head the logical chain of events, in the patient’s body, which triggered the original symptoms, the treatment strategy and execution becomes a simple matter. In this article we are going to discuss mechanism of reflex zones formatting in cases of chronic somatic abnormalities.

THE BASICS

If one touches a hot surface, hears the loud sound or dropping knife after cutting the finger while preparing the food, they activate peripheral receptors which in turn form ascending sensory inflow. In such case the electrical disturbances (or action potentials) formed in the peripheral receptors are immediately conducted to the sensory cortex of the brain. Thus the actual sense of the object’s temperature, the perception of the sound, or sensation of pain as a result of the finger’s cut are formed in the brain itself based on data previously obtained from the peripheral receptors.

As soon as sensory stimuli from the peripheral receptors were processed by sensory cortex, the brain’s motor cortex is activated, and it forms a motor response. Thus, one withdraws their hand from the hot stove, decreases volume of the knife dropping and puts a band aid on the finger. All of these are different motor responses to initial sensory stimulation of the brain by peripheral receptors.

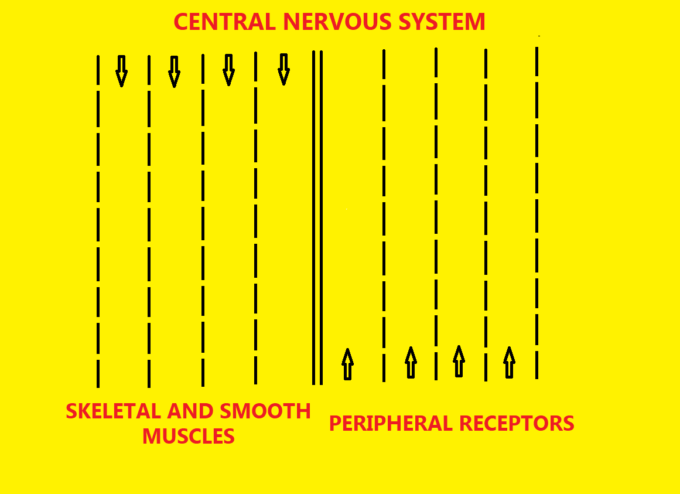

We can make an analogy of the main control system of our body with the two-way traffic on the highway (see Fig 1). Each peripheral and spinal nerve which connects tissues and organs with the brain and spinal cord is the 24 hours functioning highway which transfers information back and forth.

If, we further extend the analogy that each electric signal generated in the peripheral receptors or in motor cortex is a ‘car’ which follows the highways: south to north traffic along the highway brings information from the peripheral receptors to the central nervous system (CNS) while north to south traffic along the opposite side of the same highway delivers CNS’s motor response to sensory stimulation originated in the tissue and organs.

Taking the highway analogy even further, imagine that a small accident happened on one lane of a very busy 5-lane highway. You notice that traffic slows. If an accident is larger and police shut down two or three lanes, a bottle neck traffic jam forms or traffic completely stops. This simple analogy defines the entire reflex zones concept and misleading effect it has on the clinical symptoms and treatment strategy if the therapist doesn’t have a full understanding of the mechanism behind reflex zones formation.

Let’s review an example from a potential patient with symptoms of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) which is very common these days. Each patient with CTS exhibits exactly the same set of symptoms in different combinations and intensity: tingling and later numbness along palmar surfaces of 1st and 4th fingers, feeling cold in the palm, quick fatigue and hand and especially thenar’s muscle weakness. In advanced stages of CTS, muscles atrophy making it difficult to execute even simple everyday tasks like buttoning a shirt.

The clinical picture of CTS can be the result of tension build up within carpal tunnel itself and in this case the local therapy must be implemented to decompress the median nerve within the carpal canal. However, in a great number of clinical cases the patient presents CTS lookalike symptoms which are the results of completely different abnormalities. In these cases, CTS is reflex zones formation rather than the actual cause of the symptoms. Now it is a professional mistake to start work on the carpal tunnel itself while the real trigger is in a completely different part of the body. Only after each potential trigger is ruled out the therapist should work on the wrist itself.

Let’s discuss this confusing situation in detail. The diagram below explains symptoms similar to CTS, but caused by other triggers which can be easily interpreted as CTS itself. Before you turn the animation on (push play button below the diagram) let’s look first at what is on the diagram.

Five blue strips with gaps present the median nerve which supplies our palm working in four different clinical scenarios indicated on the left side of diagram: norm, mild nerve irritation, nerve compression, nerve transection and neuroma formation as a result of it. Median nerve as any peripheral nerve consists from: axon, myelin and endo-/perineurium (they are indicated). Peripheral receptors on the palm are indicated on the diagram as well. Also, along the upper border you may see vertical dashed lines which indicate different parts of the same nerve while it passes from the hand to the anterior neck and all way to the spinal cord.

Let’s examine clinical events when symptoms of the CTS are result of reflex zones formation rather than tension built up within carpal tunnel itself. Let’s take as an example the tension formed on the anterior scalene muscle (ASM) in the anterior neck. In such case the real trigger of the CTS symptoms is tensed ASM affecting part of the brachial plexus which gives origin to the median nerve. Observe the movements of the dots on the diagram below.

Normal Function of the Median Nerve (first part of the animation)

Let’s say that a person tried to detect the temperature of the surface which was directly under sunlight for some time. He or she touches the surface with the palmar part of the hand and immediately temperature receptors are activated and they are firing signals to the sensory cortex and brain forms perception of the surface’s temperature based on the obtained data. In the diagram you see yellow dot (signals from the peripheral receptors) move quickly along the median nerve delivering data to the spinal cord.

Mild Irritation of the Median Nerve on the Anterior Neck by the Anterior Scalene Muscle (second part of the animation)

Now ASM slightly increases its resting muscle tone and mild tension is formed which is an extremely common scenario. As a result of ASM losing its softness, even during its complete relaxation, muscle starts to mildly irritate part of the brachial plexus which gives origin to the median nerve. The peripheral receptors on the palm are still working fine and they continue to send their signals with normal rate and speed (fast moving yellow dot). However, when these signals are reaching level of the ASM in the anterior neck there is ‘traffic jam’ since a lesser number of signals (smaller red dot moves up) is getting through the irritated and mildly inflamed nerve to the CNS. The brain interpreted that as a tingling on the palm.

The patient with this situation will exhibit classical symptoms of CTS while there are not any complaints or symptoms on the neck itself. The therapist who decided to use local therapy on the wrist for this patient is only going to patch the problem without decisive elimination of the symptoms.

Why does mild irritation of the median nerve in the anterior neck triggers secondary reaction as CTS while there are not any symptoms on the neck? If any spinal or peripheral nerve is mildly irritated the symptoms of it are going to appear first at the end of its innervation and in case of the median nerve it is the palmar surface of the hand. Thus, we described the clinical picture of Anterior Scalene Muscle Syndrome which presents itself as CTS. Only a detailed evaluation allows avoidance confusion and incorrect treatment strategy.

Severe Irritation/Compression of the Median Nerve on the Anterior Neck by the Anterior Scalene Muscle (third part of the animation)

The same patient, who sometimes for months complained about CTS symptoms, sneezes, lifts heavy object, or gets into a car accident; suddenly the pattern of pain changes dramatically: the patient feels that entire arm, forearm, and hand are on fire, there is constant electric shock type of the pain which radiates from the neck along the entire upper extremity, there is severe muscle weakness etc. At this point seeing a PT or massage therapist is last on the patient’s mind since he or she is in emergency room and nobody is going to consider CTS as clinical problem because the patient clearly established a link between neck and symptoms along the upper extremity all way to the hand.

The third part of animation illustrates this scenario. Readers may see the entire median nerve from the hand to the anterior neck presented as a faded image. This illustrates the fact that now the entire median nerve is compromised, and the patient feels symptoms along the hand, forearm and arm. Since function of peripheral receptors in all these areas is now greatly affected, an even smaller number of action potentials are able to reach the spinal cord (slow moving small red dot) because of severe nerve compression and local inflammation on the level of anterior neck. That further diminishes the flow of the sensory signals to the brain and sensory cortex sees that as a disaster.

This patient exhibits a severe clinical picture of burning and electric shock pain, significant muscle weakness and various circulatory abnormalities. This is the clinical picture of Anterior Scalene Muscle Syndrome turning into the Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. It is same problem but its’ different intensity produces completely different clinical picture compared to the previously discussed one.

Transection of the Median Nerve (fourth part of the animation)

The final stage of the nerve trauma is its direct transection by the trauma. If the nerve is cut completely the nerve tissue below the complete transection degenerates and atrophied nerve forms an enlargement called neuroma.

Let’s come back to the clinical pictures of Anterior Scalene Muscle and Thoracic Outlet Muscle Syndromes. In both cases the cause is the same: tension in ASM but in the first scenario it shows itself as CTS and in the second as a blooming picture of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. Thus, the difference is only in the degree of nerve compression and inflammation. If the patient with ASM Syndrome is going to be treated as CTS, which is very frequently the case, the patient eventually is going to undergo unnecessary hand surgery or Thoracic Outlet Syndrome is going to develop later on.

In the diagram we discussed how tension in the anterior neck is going to trigger symptoms of CTS while the real cause is tension in ASM. However the clinical reality is even more complex because there are 6(!) completely different causes (ASM is just one of them) which are responsible for the exactly same clinical picture of CTS:

1. Intervertebral disk pathology on the level C5-C7 (Pierre-Jerome and Bekkelund, 2003)

2. Tension in the posterior cervical muscles on the same levels (Kane, 1994)

3. Anterior Scalene Muscle /Thoracic Outlet Syndromes (Vaught et all, 2011), Pectoralis Minor Muscle Syndrome (Langley, 1997)

4. Pronator Teres Muscle Syndrome (Werner et al, 1985)

5. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Thus, the therapist faces the necessity to differentiate and correctly choose one of six completely different treatment protocols. If the therapist lacks evaluation skills and is unable to identify the initial trigger his or her therapy is going to fail and the therapist becomes another failure in the long line of other health practitioners who tried to solve this case before. Eventually the patient undergoes a completely unnecessary hand surgery which may greatly affect the patient’s life while similar or even worse symptoms continue to be present.

In Part III of this article, we will discuss reflex zones formation in the soft tissues as a result of chronic visceral disorders and how reflex zones elimination helps to stabilize further development of chronic visceral disorders.

REFERENCES

Burch R.C., Loder S., Loder E., Smitherman T.A. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015 Jan;55(1):21-34.

Kane E.J. More on Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. J Athl Train. 1994 Sep; 29(3): 197.

Langley P. Scapular instability associated with brachial plexus irritation: a proposed causative relationship with treatment implications. J Hand Ther. 1997 Jan-Mar;10(1):35-40.

Pierre-Jerome C, Bekkelund SI. Magnetic resonance assessment of the double-crush phenomenon in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome: a bilateral quantitative study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2003;37(1):46-53

Vaught MS, Brismée JM, Dedrick GS, Sizer PS, Sawyer SF. Association of disturbances in the thoracic outlet in subjects with carpal tunnel syndrome: a case-control study. J Hand Ther. 2011 Jan-Mar;24(1):44-51

Werner CO, Rosén I, Thorngren KG. Clinical and neurophysiologic characteristics of the pronator syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985 Jul-Aug;(197):231-6.

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: 2020 Issue #3