By Dr. Ross Turchaninov, MD

Very frequently, an initial visual observation gives vital clinical clues, which should be confirmed later during the patient’s evaluation. Here is the picture of our 82-year old patient who came to the clinic complaining of left side lower back pain all the way to the lateral aspect of the leg and top of foot.

A first look at the patient indicated that he has bilateral knee Osteoarthritis (OA) with varus deformation more prominent on the right. Looking on the position of his left arm and pelvis it is obvious that he also has pelvis tilt and outward rotation to the left.

From a purely clinical observation, one may suspect that knee OA is the cause of his clinical symptoms. Indeed, further evaluation confirmed that his Lower Back Tension complicated by Common Peroneal Nerve Neuralgia, resulted from bilateral OA and shortening of the right leg due to excessive varus in the knee. This shortening caused pelvis tilt, spasm in lumbar erectors, and quadratus lumborum muscles with following compression of the L5 spinal nerve and symptoms of Common Peroneal Nerve Neuralgia down to the leg and foot.

Due to his advanced age and general health problems, knee replacement surgery is unrealistic. We suggested the following program to our patient:

- Medical Massage therapy to decompress soft tissues in the lower back, eliminate pelvic tilt, pain, and dysfunction

- Wearing shock-absorbing sneakers with gel inserts, placing an extra insert into the left shoe to compensate for the shortening of the left lower extremity (due to more significant varus deformation

- Therapeutic exercising in the pool

- Daily stretching routine for the knees and lower back

- Daily application of TENS unit altering knees (10 sessions per month) at home,

- Voltaren gel (over the counter cream) at night.

Five sessions of Medical Massage protocol eliminated his lower back pain and symptoms of neuralgia. The patient continued faithfully with a suggested in-home support system once per month for supportive Medical Massage sessions. It is five months now, and he does not have any pain or discomfort in his lower back and knees. Of course, he continues to have some ROM restrictions in the knees due to joint degeneration, but we are confident that the program will prevent future deterioration of his knees.

Of course, the visual observation provided just the first clue, and it is not enough to formulate MM treatment strategy. However, observation delivers the first precious piece of clinical data, which should be confirmed or ruled out by questioning and further testing.

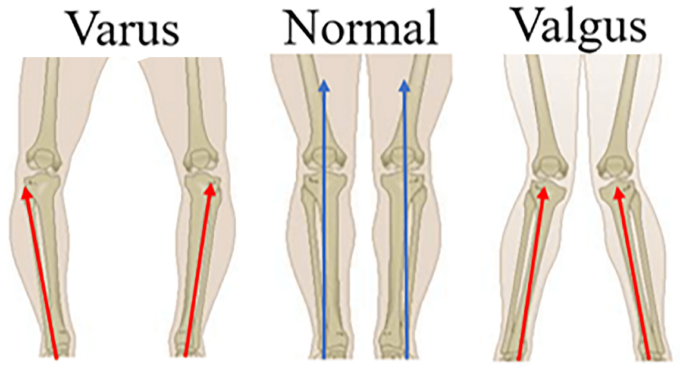

Let’s look at varus/valgus deformities of the joints and estimate the clinical value of this simple sign. Fig. 2 illustrates the regular, varus, and valgus arrangement of the knees.

Fig. 2. Knee arrangement

As you may see, varus deformation is when bones that form joints (knee in the picture) are arranged at the angle which opens inwards. Valgus deformation is the opposite since bones that form joints are positioned in the angle that opens outwards. Knee varus/valgus deformities can be results of:

1. Physiological, for example, females with wider pelvis typically have the valgus arrangement of the knees.

2. Inborn deformity (e.g., Genu Valgum)

3. Varus/valgus foot arrangement

4. Results of the trauma to medial (valgus) or lateral (varus) collateral ligaments. These ligaments stabilize our knees in correct alignment and prevent excessive varus or valgus deviations. However, the patient must have a history of severe knee trauma to develop such instability.

5. Type of activity (varus knee deformation in horseback riders)

6. Obesity results in valgus deformities of the joints in the lower extremities (Soheilipour et al., 2020)

7. Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), Gout, Psoriasis, etc.

Let’s concentrate on OA and RA. Older patients with OA have a tendency to form varus deformation in the affected joints (Lu et al., 2019), as our patient exhibited. At the same time, excessive valgus deformation of the affected joints is a clinical sign of Rheumatoid Arthritis (Brewerton, 1957). Fig. 3 illustrates a patient with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), which has affected the joints of both lower right extremities. Compare it with the joint arrangement in our patient in Fig.1.

Fig. 3. Valgus deformation of all joints of the right lower extremity

You may observe valgus deformation in the patient with RA in the knee, ankle, and first metatarsophalangeal joints. Her bones in each joint form an angled outwards (indicated by red markers).

Besides detecting varus/valgus deformation of the joins, it is important to understand the role these deformations are playing in the patient’s posture and movements. The case of our patient is a great example because varus deformation of the knees was the initial trigger of his lower back pain and peripheral neuralgia.

Medical Massage therapy is an important treatment option for patients with OA and RA. However, approaches to therapy are completely different for these two groups of patients. Failure to understand the basic principles of somatic rehabilitation of patients with OA and RA may worsen the original clinical picture.

The main differences:

1. Timing of the therapy.

For patients with OA, there is no restriction in MM therapy. The treatment of patients with RA can be done ONLY during stable remission, and the patient’s rheumatologist must be informed.

2. To help the patient with OA, the therapist must address soft tissues layer by layer, including the periosteum of the bones, and use intra-articular therapy when joints’ space is directly available. Periosteal Massage is especially effective for the cases of OA.

For the patient with RA the therapist must concentrate on Lymph Drainage Massage first and later work ONLY on the soft tissues surrounding the joint. The therapist should stay away from the periosteum and from the joint’s space itself. Thus, Periosteal Massage is contraindicated. Any additional therapy may trigger a severe flare-up of RA.

3. For the patient with RA, the earliest prevention of joint contractures AND maintenance of ROM are critically important parts of rehabilitation. For the patient with OA, maintenance of joint ROM is a critical component.

4. Treatment intensity is another essential aspect. In cases of OA the treatment intensity can steadily rise from session to session, and breaks between sessions should last one or two days. In cases of RA, the therapist must be very gradual and careful. Everything must be done within the patient’s comfort, and building clinical response takes more time and patience. In cases of RA, it is better to undertreat the patient than overdo it. Breaks between sessions must be longer, starting once a week, and massage sessions should not exceed twice per week. The therapist must communicate with the patient to figure out when it is time for the next session.

REFERENCES

Brewerton, D.A. Hand Deformities in Rheumatoid Disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957 Jun; 16(2): 183–197.

Lu Y., Zheng Z., Chen W., Lv H., Lv J., Zhang Y. Dynamic deformation of femur during medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. PLoS One. 2019; 14(12): e0226795.

Soheilipour F., Pazouki A., Mazaherinezhad A., Yagoubzadeh K., Dadgostar H., Rouhani F. The prevalence of genu varum and genu valgum in overweight and obese patients: assessing the relationship between body mass index and knee angular deformities. Acta Biomed. 2020; 91(4): e2020121.

For Dr. Ross Turchaninov’s bio please click here: https://www.scienceofmassage.com/editorial-board/

Category: Medical Massage

Tags: 2021 Issue #2