By Dr. Ross Turchaninov

In issue #1, 2012 of JMS we published “The Science Of Clinical Interview.” This article was met with great enthusiasm by the massage community and many therapists successfully use the Clinical Interview Form we developed for massage practitioners.

This is the second article in a series on clinical evaluation of patients. Its topic is the Visual Evaluation (VE) of patients, which starts during first contact between the therapist and the patient and continues immediately after the Clinical Interview. Very frequently VE gives the therapist the first important clues about the case he or she faces and helps with formulation of a successful MEDICAL MASSAGE PROTOCOL. There are several principles of VE.

OBSERVE THE WAY THE PATIENT MOVES

This is the first glimpse of what the therapist may be dealing with. The most efficient way to observe the patient’s body mechanics is to see how he or she moves without seeing you. If you have free time before the session and are able to look outside or along the corridor, pay attention to the patient’s gait and posture while the he or she walks to your office. Does the patient limp? Use a cane or walker? Does the neck or lower back look stiff? Does the patient’s head tilt forward or does he support his arm while walking?

Some patients subconsciously will try to cover their ailments in front of the therapist while others will exaggerate them. Observing the patient without being seen eliminates those factors. If you don’t have the ability to observe the patient without being seen, start VE as soon as you first encounter the patient. Again pay attention to how they’re getting up from the chair, walking and its pace, and body mechanics.

This first encounter gives you priceless clinical information. For example, you see that the patient slightly limps on the right side and while she walks one foot is turned laterally while the other foot is positioned correctly. This is Freiberg’s Sign, which gives the therapist 100% accurate information that the patient has tension in the piriformis muscle. To reduce irritation or prevent possible pressure on the sciatic nerve by the tensed piriformis muscle, the patient’s brain rotates her foot laterally during every step as a compensatory reaction. The video below illustrates Freiberg’s Sign.

Here is another clinical example: the patient sits without any visual postural abnormality. However, as soon as he gets up and starts to walk, his left shoulder becomes visually elevated and his head tilts slightly to the left. During the clinical interview the patient said that he had a severe headache on the left side of his head. Elevation of the left shoulder while the patient walks is the sign that spasm in the left levator scapulae muscle contributed to the posterior cervical muscle tension, which in turn is responsible for the tension headache. To decrease the intensity of the headache the patient’s brain makes adjustments in body mechanics to elevate the shoulder on the same side and laterally tilt the head. It helps to decrease tension in the levator scapulae muscle. Since the levator scapulae muscle works harder to stabilize our head while we are walking, this shoulder elevation becomes visible only when the patient moves and it disappears while he is at rest. Figure 1 illustrates this case from our clinic.

Fig. 1. Spasm in the left levator scapulae muscle

a – normal head and shoulder position while the patient sits

b – lateral tilt and left shoulder elevation as a compensatory reaction

Red lines indicate position of the shoulders

For the patient with Intercostal Nerve Neuralgia any change in the body position (e.g., raising arm to shake hands during an introduction) will trigger pain in the chest or middle back, which the practitioner may observe as a facial expression of discomfort. This will be accompanied by shallow breathing since every deep inhalation triggers the pain.

THE EMOTIONAL STATE OF THE PATIENT

The emotional state of the patient affects the outcome of the therapy. Patients with chronic pain usually look depressed and sometimes even their hand shake is weak. They are tired from the many ineffective therapies they’ve already tried and some are losing hope. Patients with Fibromyalgia are great examples.

In contrast, the behavior of patients with newly developed cases of somatic pathology accompanied by acute pain seem more anxious and restless than depressed. In the first case the therapist must be forceful in convincing the patient that finally there is light at the end of the tunnel. In the second case the therapist must calm the patient and eliminate anxiety and stress by having a more calming and relaxing conversation. The patient must feel that what he has requires attention, but it is fixable.

This is the subject of a separate article, but we think it’s worth at least mentioning here.

POSTURAL EVALUATION

The practitioner must evaluate the patient’s posture and ROM. Here is an example of the clinical value of postural evaluation from our clinic. Figure 2a illustrates a case of lower back pain due to acute spasm in the quadratus lumborum muscle while Figure 2b illustrates a case of lower back pain due to acute spasm in the lumbar erectors.

Fig. 2. Postural changes in cases of lower back pain

a – acute spasm in quadratus lumborum muscle

b – acute spasm in lumbar erectors

Both patients have acute right side lower back pain. ROM in the lower back in both cases is severely restricted. In both patients the pelvis is elevated on the right side. Both are tilted to the right. Despite these obvious similarities, comparison of the two pictures indicates great postural differences. As you see, the patient with acute spasm in the quadratus lumborum muscle exhibits much more violent deformation, which doesn’t go away even in the horizontal position (Fig. 2b). In contrast, the patient with acute spasm in the lumbar erectors exhibits less severe deformation and while in the relaxed horizontal position the tilt can be self-corrected (Fig. 2a).

Here is important information to remember for everyone who would like to be successful with clinical application massage therapy. From countless articles, seminars, webposts, etc., we observe the same mistakes which are now widely circulated in the massage community. Many educators constantly pound therapists with recommendations to do postural analysis and base therapy on their findings. The tilt of the pelvis, elevation of the shoulder, protruding neck etc., are considered critical factors in the development of a treatment strategy. Various charts and wall posters are sold to therapists which help to detect postural abnormalities and design therapy accordingly.

This is an absolute mistake! For the sake of your patients, don’t fall for these now common mistakes. Yes, the postural changes must be examined and we advocate that. However, the postural changes never should be the sole foundation for the treatment protocol. These changes the practitioner sees or tries to detect are protective reactions generated by the brain to eliminate or diminish pain or other pathological symptoms.

Yes, detect and even record pathological postural changes. But never rely on them alone while developing treatment strategy! These changes must be evaluated only in conjunction with other symptoms which are much more valuable in the majority of clinical cases.

ACTIVE RANGE OF MOTIONS (AROM)

Active ROM is movement in the joint or spine conducted by the patient under the therapist’s guidance and observation. While examining AROM the therapist must first ask the patient to stop movement when he or she feels the first sensation of pain or discomfort and after that continue to maximum movement through the pain and discomfort (if it is possible). The video below illustrates the evaluation of AROM for a patient with Sumacromial Bursitis in the left shoulder.

As you can see in the first part of the video, the patient stops when she starts to feel the first sensations of pain during active abduction in the left shoulder. Further increase of active abduction triggers the acute pain and to execute the therapist’s command of further abduction the patient elevates her entire left shoulder rather than actively abducting her arm in the shoulder joint, which she does normally on the right side.

What is the diagnostic value of this two-step evaluation of AROM? The earlier the patient feels pain while executing AROM the more complex the case the therapist faces. This piece of information reflects on the number of sessions needed. The secondary compensatory reaction (elevation of the shoulder on the same side) which the patient engaged in during active abduction informs the therapist about the necessity to examine the patient’s trapezius and levator scapulae muscles which more likely harbor secondary trigger points.

EVALUATION OF THE SKIN

The next step is evaluation of the skin. To conduct that correctly the therapy room must have bright light which can be dimmed later. There is no way skin can be examined and cutaneous reflex zones detected without proper illumination. The therapist looks for several clues:

1. Paleness of the skin

The paleness of the skin is a result of reflex vasoconstriction and it is a sign of cutaneous reflex zones formed due to disbalance between the activity of sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system.

One of the common examples is Raynauld’s Phenomenon when patients exhibit severe vasoconstriction and pain in the fingers and hands under the stress or during exposure to low temperatures.

The presence of the paleness of the skin indicates a decrease in the parasympathetic nervous system activity and it will require application of more intense massage techniques during the treatment – friction, percussion, manual vibration.

Also, paleness of the skin may develop as a result of circulatory abnormalities, e.g., Buerger’s Disease.

2. Loss of hair

Paleness of the skin is frequently accompanied by the loss of skin hair. This sign is noticeable in males especially in the lower extremities. Lack of proper tissue oxygenation damages hair follicles and it contributes to the loss of hair.

3. Redness of the skin. Brown discolorations

Skin redness can be caused by two factors: insufficient venous drainage (e.g., varicose veins) and local inflammation in the skin (e.g., infection), underlying tissues (e.g., cellulitis) or anatomical structures (e.g., knee synovitis). Chronic insufficient venous or lymph drainage eventually triggers brown discolorations first in the form of spots, which later compile together and completely change the skin color to brown in the affected area. The more extended the brown pigmentation the more problems with drainage the patient has. Fig. 3 illustrates brown pigmentation of the left leg developed as a result of peripheral edema.

Fig. 3. Pigmentation of the left leg

4. Peripheral edema. Skin reflects light

There are many causes of peripheral edema. Large peripheral edema is easy to detect because it is obviously visible. Before treatment starts the practitioner must ask the patient if the cause of the edema has been established.

Hidden edema is more difficult to detect. This is why the sign of light reflection by the skin can be the first indication that hidden edema is slowly developing in the soft tissues due to insufficient venous or lymphatic drainage. Figure 4 illustrates significant peripheral edema on the leg with skin reflecting light in the middle of the leg.

Fig. 4. Peripheral edema on the left leg

Red arrows indicate the sign of light reflection. The presence of peripheral edema and skin discoloration requires adding Lymph Drainage Massage into the treatment protocol.

5. Stretch marks

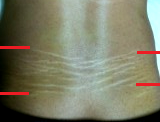

If stretch marks are located in unusual areas, especially if these areas are associated with the chronic pain, they can be a sign of cutaneous reflex zones. Figure 5 illustrates stretch marks developed in one of our patients who for years suffered from chronic lower back pain.

Fig. 5. Stretch marks in the lower back due to chronic lower back pain

Red lines illustrate the borders of the stretch marks on the right and left sides.

The presence of stretch marks does not automatically mean the presence of cutaneous reflex zones. Stretch marks can develop as a result of pregnancy, sudden weight gain, accelerated growth during puberty, etc. Some females have them on the hips and buttocks areas.

The therapist should look at stretch marks formed in unusual areas especially if these areas are associated with chronic pain. Our patient (see Fig. 6) didn’t gain weight, and according to him these marks started to appear approximately 10 years ago but he has suffered from bi-lateral chronic lower back pain since his teen years. His left side was more affected and as you can see in Fig. 6, the stretch marks are slightly more prominent on the left side. Further examination confirmed the initial visual evaluation that these stretch marks are the result of reflex zones formation.

How can stretch marks develop in cases of chronic pain? They are a result of chronic irritation of the cutaneous nerves which supply the skin. With time this affects the skin’s structure and function since chronic vasoconstriction contributes to the fragility of collagen fibers. The weaker collagen fibers decrease elasticity of the skin and with time they can break, contributing to stretch mark formation.

In summation, we would like to emphasize that the signs and symptoms we discussed above should be considered only as additional clues. The effective clinical evaluation and development of efficient MEDICAL MASSAGE PROTOCOLs requires the analysis of all information obtained during interview, visual and palpatory evaluations.

In subsequent articles on patient evaluation we will discuss the science of palpation as well as tests to separately examine and detect reflex zones formed in the skin, fascia, skeletal muscles and periosteum.

Category: Medical Massage